Note: This section may contain the names and images of deceased people. We treat Indigenous culture and beliefs with respect. We acknowledge that to some communities, it is distressing and offensive to show images of people who have died.

If anybody finds items which they find distressing and offensive, we ask them to notify us.

Article in The Age newspaper:

REPORTS of an apartheid-style practice of separate entrances for indigenous people at some Australian hospitals have drawn criticism from a United Nations investigator.

Anand Grover, the UN's special rapporteur on health, has raised the issue of dividing screens at hospital entrances in a report critical of the Northern Territory intervention and indigenous health performance.

He said he had been told that hospital authorities ''reinforced stereotypes and prejudice … by installing screens and walkways to allow non-indigenous people to access hospitals without seeing indigenous families sitting at the entrance''.

A spokeswoman for the federal Department of Health said hospitals were subject to anti-discrimination laws like any other institution.

Mr Grover stood by his statements yesterday, but would not identify his source nor any hospitals with separate entrances.

''I think it is very serious because it reminds me of apartheid,'' he told The Age.

Paul Bauert, the president of the Australian Medical Association in the Northern Territory, said that in recent years the Royal Darwin Hospital had had a separate entrance where Aboriginal patients and their families could gather, as was their custom.

The separate entry had gone as a result of a building redesign.

The president of the Australian Indigenous Doctors Association, Associate Professor Peter O'Mara, said he had not heard of race-based separate entrances, but if they did occur, ''it is pretty poor''.

The federal Labor government has decided that the last resort for getting Northern Territory Aboriginal children to attend school is to cut their parents' Centrelink payments. The poorest people, those Australians who are totally reliant on Centrelink, will be subject to suspended legal income support. How will the children be fed if there is no money in the home?

Legislation to put this into effect was introduced into Parliament yesterday. As a former, long-serving senior public servant, I see this as the last straw in Aboriginal affairs policy. I am absolutely opposed to it. This is bad public policy, it is morally objectionable, and it will not work.

It's time for all ALP politicians to oppose this proposed legislation. How can any true Labor member support such an illogical policy? Surely such punitive measures are not supported in Labor heartland. I cannot believe that Gough Whitlam, Bob Hawke, Paul Keating or even Kevin Rudd, especially after his national apology to us, would have allowed such ill-founded policy to even get out of Jenny Macklin's and Peter Garrett's offices, let alone be endorsed by cabinet.

The independents and the Greens also need to stand up against this proposed legislation.

Where is the evidence-based policy to support this legislation? This legislation is based on a pilot scheme being run in schools at Ntaria (also known as Hermannsburg), Wadeye, Tiwi Islands, Katherine and its town camps, and Wallace Rockhole. The pilot scheme has all but failed. School attendance has not changed markedly. There are no indisputable positive results. Evidence-based policy has disappeared into thin air. One rarely hears any MP citing it when talking about Aboriginal affairs these days. And that's because there isn't any.

Evidence-based policy is what we as Aboriginal people were promised emphatically by the ALP government. As ever, we are still waiting.

In my long experience, exceeding 40 years working in Aboriginal affairs at the local, regional and national levels, I have never known Aboriginal children to have access to fully resourced and fully staffed schools in the remote communities in the Northern Territory.

It would be much more effective to spend the multiple millions of dollars on fully staffing remote schools with experienced teachers who have already worked with Aboriginal people, rather than employing fly-in, fly-out truancy officers. It should be compulsory for teachers assigned to work in a remote Aboriginal community to undertake a thorough background briefing on the history of the community and its present composition and profile. Every teacher should receive accredited cross-cultural training before even moving to the community. The government has long recognised the need to provide better incentives for doctors to work in regional and remote areas, so why not for teachers too?

A concerted effort is needed to train local Aboriginal people to be fully qualified teachers in their own right. This is the only way to stabilise the teaching workforce in remote areas, making school attractive for the children. The government is clearly focused on employment/workforce participation for all Australians. Jobs for qualified Aboriginal people resident in remote communities should be a high priority. Where are the intensive training programs for our own people to become fully qualified teachers? In our remote Aboriginal communities our cultures are resilient and our languages are still in everyday use. The abolition of bilingual education has been a shame. It should be a choice available to communities. Service delivery in remote areas is costly. So, too, has been the loss of our languages and culture, so entwined with our land. Surely Aboriginal people have lost so much already that a decent education for all our children is not too much to ask.

This legislation must be withdrawn. Ministers Macklin and Garrett should go back to the drawing board to find evidence-based policy to show you what will work. Let's not waste any more taxpayers' money on using yet another stick to penalise the poorest people in our own land.

Pat Turner, an Arrernte/Gudanji woman living in Alice Springs, is former deputy secretary of the Commonwealth Departments of Aboriginal Affairs and Prime Minister and Cabinet. She is also a former CEO of ATSIC and former deputy CEO of Centrelink.

Article in The Age:

KIM Sattler may not be known to Julia Gillard, but her face must be familiar to many in Canberra Labor circles.

The mother of two, who ran unsuccessfully as a Labor candidate for the territory seat of Molonglo in 2004, is a director of the National Museum of Labour, a project which tells the story of Australian workers.

Newspapers yesterday published pictures from the union official's Facebook page, which included some of Ms Sattler with Labor luminaries including Ms Gillard and veteran senator John Faulkner.

As secretary of Unions ACT, Ms Sattler has acted as a conduit between unions - including 24 unions with 30,000 members - and a range of environmental and social justice groups.

During US President Barack Obama's visit to Canberra last November, she addressed a rally on the lawns in front of Parliament House questioning the value of the US alliance. In August, she addressed a pro-carbon tax rally, and suggested truck drivers involved in the anti-carbon tax convoy of no confidence had been paid to participate.

In December 2010, she addressed a rally for WikiLeaks founder Julian Assange in which she said the Australian government had given him less support than they gave to drug traffickers.

Despite having Jewish great-grandparents, she called for a boycott of Israeli-made goods in protest at Israel's 2010 raid on a flotilla of ships that was attempting to break the blockade of the Gaza Strip.

She has also worked for gay rights, advocated for more humane treatment of asylum seekers and protested against Iran's suppression of demonstrations.

She has had a long association with the Aboriginal tent embassy, which receives support from the union movement. She told reporters over the weekend she has acted as a liaison between police and activists and helped arrange essentials such as rubbish collection. In August 2007, she was the main speaker at a tent embassy rally against the Northern Territory intervention.

Ms Sattler was elected secretary of Unions ACT in November 2006.

Letters in The Age 300112 and 310112

ABBOTT'S suggestion that we have moved on from the issues which caused the tent embassy to be set up (The Saturday Age, 28/1) displays an ignorance of indigenous circumstances that is symptomatic of right-wing politics. If the embassy were no longer relevant, it would mean indigenous and non-indigenous Australians had equal standards of health care, education and infrastructure. Textbooks would present a balanced view of history, including indigenous perspectives, rather than tokenistic white imaginings of the Aboriginal experience. The constitution would acknowledge this land's original owners and we would have stronger laws to uphold traditional land claims of their descendants. There would also be legislation that safeguarded spiritually significant sites and cultural artefacts, and delivered stricter consequences for non-compliance.

Alethea Kinsela, CollingwoodFOR many, the flag is a symbol of genocide and dispossession. How can people be outraged about Gillard's stolen shoe, yet forget that indigenous communities have had land stolen from them since 1788? I support the tent embassy and find it inspiring that its leaders continue to take a stand against the racism rife in this country.

Jenn Winterbine, St KildaLetter in The Age 310112

ON AUSTRALIA Day in 2008, an indigenous man, Mr Ward, was arrested in Western Australia and transported 360 kilometres in a prison van with no working airconditioner. With temperatures in the van reaching 50 degrees, he collapsed and died. The WA coroner found that Mr Ward died a "ghastly" death and essentially was "cooked". Did the people who have written letters to newspapers and called talkback radio over the past few days to express outrage over the "violent" demonstrations by Aboriginal people feel equally outraged over what happened to Mr Ward? Did they express that for such an horrendous event to happen on our "national day" was unacceptable? Was it the front page headline in our national papers for three days running?

I am sick of the fact that so many people in our society are always so much more offended by the protests about social problems than the social problems themselves. Tony Abbott may think we've come a long way in 40 years, but many Australians, both indigenous and non-indigenous, would vehemently disagree with him.

Jane Thomas, Belgrave

From Opinion page in The Age:

Rejecting discrimination in the constitution would empower us all.

There are examples where Aboriginal people have resisted attempts by the state and others to trample their rights without resorting to violence and the use of brute force. Noonkanbah in the Kimberley and the tent embassy in Canberra spring to mind, though recent events in Canberra may have tainted this perspective of the tent embassy for some.

It would be simplistic however, to condemn outright the behaviour of protesters associated with the tent embassy last week without considering the sense of oppression that some of our people still feel towards our governments on a whole range of matters.

I will always condemn bad manners and unnecessarily aggressive behaviour by whomever. But I will always defend people's rights to assert their political position and try to look to the heart of why people feel so oppressed that they feel violent confrontation is the only recourse to the resolution of their position.

As a nation-state, we have not succeeded in achieving a just accommodation of the truth concerning the sovereign indigenous peoples who occupied this continent before the arrival of the British.

This year I have had the privilege of working with an expert panel comprised of Australians from diverse backgrounds and political persuasions to search for ways for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples of Australia to be recognised in the Australian constitution. Our report was handed to the Prime Minister earlier this month.

The panel proposed a new head of power called section 51A. This new section would incorporate a statement of recognition similar to a preamble, and also give the Commonwealth Parliament the power to pass laws for Aboriginal and Torres Islander peoples. The panel also recommended a non-discrimination provision (section 116A) be inserted in the constitution.

This is not a one-clause bill of rights. Nor is this proposition something that is radical or new. Such a provision would bring us into step with international standards.

The expert panel has been criticised for over-extending its reach by proposing such a recommendation. There will, of course, be some who argue against and some who argue in favour for such a provision.

I hope, however, that we as a nation can have an informed and mature conversation about such matters, without resorting to divisive commentary or cheap political point scoring.

Australians generally do believe in justice and tolerance and are not racist, but we are perhaps too accepting of the racism and intolerance in our midst. The terrible attacks on Indian students, the demonising of Muslims and the Cronulla riots tell us how far we still need to go to address racism and intolerance in our society.

The intolerance and racism is something that many indigenous people are confronted with on a daily basis.

We have seen the demonising of our cultural identity and ridiculing of our traumatic history by Australia's political leaders who label the ''indigenous rights agenda'' as meaningless symbolism that has no positive practical outcomes.

What we have not seen is an honest dialogue about the impacts of the settler state and its intertwined history with us. What we do see are the consequences of modernity upon our ways, cultures and spiritual values. This is why a dialogue is essential. I believe that racial discrimination should not be tolerated in our society, and enshrining this in our constitution would be an act that enhances us all.

Patrick Dodson is chairman of the Lingiari Foundation. This is an edited version of the Mahatma Gandhi Inaugural Oration delivered last night at the University of New South Wales.Article in The Age - 31 JANUARY 2012:

INDIGENOUS leader Patrick Dodson has mounted a passionate defence of a proposal to outlaw racial discrimination in the constitution, asserting many indigenous people are still confronted with intolerance and racism daily.

Professor Dodson also rejected claims that an expert advisory panel on constitutional recognition of Aboriginals and Torres Strait Islanders ''over-reached'' its mandate with the proposal, insisting it is neither radical nor new, and would simply bring Australia into step with other countries, including Canada, India and South Africa.

His remarks last night came as Anne Twomey, the director of the constitutional reform unit at the University of Sydney law school, warned that the ''complexity and extensive reach'' of the panel's recommendations would probably result in their failure if put to a referendum.

Delivering the inaugural Mahatma Gandhi Oration in Sydney, Professor Dodson, a co-chair of the expert panel, said he remained hopeful of an ''informed and mature conversation'' on the panel's proposal to recognise the original Australians in the nation's founding document. While commentators have said last week's ugly protest by activists from the Aboriginal tent embassy has damaged the cause of constitutional recognition, Professor Dodson said it was simplistic to condemn outright their behaviour ''without considering the sense of oppression that some of our people still feel towards our governments on a whole range of matters''.

He lamented Australia's inability to lift the vast majority of indigenous people to anywhere near parity with non-indigenous Australians on any social indicator, but questioned whether the mining boom was the answer.

''I question whether in the long term our participation in unbridled exploitation is not in fact adding to the diminishment of our custodial responsibilities to humanity, global sustainability and resilience.''

On the constitution, Professor Dodson rejected concerns raised by Opposition Leader Tony Abbott that the proposed outlawing of racial discrimination would amount to a ''one-clause bill of rights''.

''This is a relatively simple matter of recognition of the First Peoples of this land. Whilst this would be belated, it would set a new foundation for our future relationship,'' he said.

In a paper analysing the proposals, Professor Twomey said if the panel's recommendations were adopted, it would be up to a court to decide whether a law was for the advancement of indigenous Australians.

''On the whole, Australians have proved most reluctant to shift such assessments from the Parliament to the courts, as has been seen by the failure to introduce a bill of rights,'' she said.

While legislation barring racial discrimination had existed for decades, if such protections were placed in the constitution and were interpreted in unintended ways by courts, the only way of correcting the problem would be an expensive and difficult referendum, she wrote.

Professor Twomey praised the panel for avoiding the ''traps'' which would have accompanied a recommendation to recognise indigenous people in a preamble. But she said two members of the expert panel, academic Marcia Langton and legal expert Megan Davis, appeared to be going ''too far'' in suggesting defeat of their proposals at a referendum would show the world Australians were ''racists, and self-consciously and deliberately so.''

Professor Dodson said it would be better for the referendum not to be put forward if there was not bipartisan support.

Letters in The Age:

THE success of the proposals put by the expert panel to the Prime Minister for the recognition of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people and dealing with racist elements of the constitution is vital for our nation.

The 1999 referendum proposal for Australia to become a republic failed because it was complicated and contained qualifications to which the people could easily say no. As a result, the baby was thrown out with the bathwater.

In order to implement all the proposals of the panel there should be more than one referendum. The first one should have the effect of inserting a section 51A in the constitution. The wording should be simple, self-evident and guaranteed to succeed: "Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples were the first Australians."

Proposals dealing with the racist elements of the constitution can wait. Constitutional recognition of our first peoples can't.

Brian Sanaghan, West PrestonPATRICK Dodson is right to call for ''an informed and mature conversation'' in our national forums about indigenous issues and the constitution (Comment, 31/1). People generally are well disposed to indigenous Australians, their history and culture. We agree that discriminatory behaviour towards them needs to be countered, but many of us are by no means certain that the right way to do this is by tampering with the constitution. Moreover, we fear that some of those urging constitutional change are doing so for purposes of ''social engineering'' that have nothing to do with Aboriginal welfare but much to do with support for international government at the expense of national sovereignty.

Nigel Jackson, BelgraveMAKING racial discrimination illegal in the constitution would be a good step. There would be no more government funds allocated by race or culture, no race-based grounds to treat differently parents who keep their kids out of school or excuse those who commit violent crimes or damage government housing. There would be no more government surveys asking if I am Aboriginal. There would be no special treatment of any group based on the colour of their skin or their cultural identity. All Australians would be treated equally, without favour or adversity. What's not to like?

Janine Truter, The BasinMICHELLE Grattan's comments that the expert panel's recommendations on constitutional recognition are ''too radical and too complex'' to succeed are an insult to voters (''Shared values shine through the dark side of politics'', The Saturday Age, 28/1). Recognising the first peoples and expunging racism from our national rule-book should be an easy task for a modern nation in the 21st century. Or are we a nation of racists, as some would suggest? Recognition of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples is not a bridge too far but the next step in addressing the unfinished business of reconciliation and building a nation we can all be proud of.

Peter Lewis, Glen IrisFrom Opinion page in The Age:

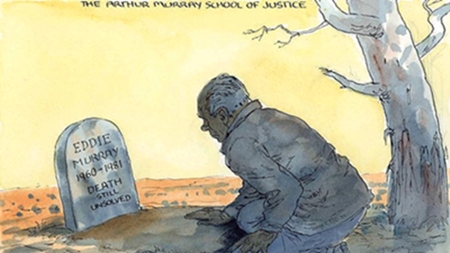

Arthur Murray was an Australian hero who spent his life pursuing the truth of his son's death in custody. But does anyone know his name?

ARTHUR Murray died the other day. I turned to Google Australia for tributes, and there was a 1991 obituary of an American ballroom instructor of the same name.

There was nothing in the Australian media. The Australian newspaper published a large, rictal image of its proprietor, Rupert Murdoch, handing out awards to his employees. Arthur would have understood the silence.

I first met Arthur a generation ago and knew he was the best kind of trouble. He objected to the cruelty and hypocrisy of white society in a country where his people had lived longer than human beings had lived anywhere.

In 1969, he and Leila brought their family to the town of Wee Waa in New South Wales and camped beside the Namoi River.

Arthur worked in the cotton fields for $1.12 an hour. Only ''itinerant blackfellas'' were recruited for such a pittance; only whites had unions in the land of the ''fair go''.

Working conditions were primitive and dangerous. ''The crop-sprayers used to fly so low,'' he told me. ''We had to lie face down in the mud or our heads would've been chopped off. The insecticide was dumped on us, and for days we'd be coughing and chucking it up.'' Arthur and the cotton-chippers made history. They went on strike, and more than 500 of them marched through Wee Waa.

The Wee Waa Echo called them ''radicals and professional troublemakers'', adding ''it is not fanciful to see the Aboriginal problem as the powder keg for Communist aggression in Australia''.

Abused as ''boongs'' and ''niggers'', the Murrays' riverside camp was attacked and the workers' tents smashed or burnt down.

Although food was collected for the strikers, hunger united their families. Leila would wake before sunrise to light a wood fire that cooked the little food they had and to heat a 44-gallon drum, cut in half lengthways, and filled with water that the children brought in buckets from the river for their morning bath. With her ancient flat iron she pressed their clothes, so that they went to school ''spotless'', as she would say.

''Who in the town supported you?'' I asked Arthur. He thought for a while. ''There was a chemist,'' he said, ''who was kind to Aboriginal people. Mostly we were on our own.'' Soon after the cotton workers won an hourly rate of $1.45, Arthur was arrested for trespassing in the grounds of the RSL Club.

His defence shocked the town; it was land rights. All of Australia was Aboriginal land, he said.

On June 12, 1981, Arthur and Leila's son, Eddie, aged 21, was drinking with some friends in a park in Wee Waa. He was a star footballer, optimistic of touring New Zealand with the Redfern All Blacks rugby league team. At 1.45pm he was picked up by the police for nothing but drunkenness. Within an hour he was dead in a cell, with a blanket tied round his neck.

At the inquest, the coroner described police evidence as ''highly suspicious'' and records were found to have been falsified. Eddie, he said, had died ''by his own hand or by the hand of a person or persons unknown''. It was a craven finding familiar to Aboriginal Australians. Everyone knew Eddie had too much to live for.

Arthur and Leila set out on an extraordinary journey for justice for their son and their people. They endured the ignorance and indifference of white society and its multi-layered political and judicial bureaucracies. They won a royal commission, only to see the royal commissioner, a judge, suddenly appointed to a top government administrative job in the critical final stages of the hearing.

They eventually won the right to exhume Eddie's body, and suffered terribly in the process, in order to prove the true cause of death, and they proved it; his sternum had been crushed by a blow while he was alive. And they reaffirmed how common their story was. ''They're killing Aboriginal people … just killing us,'' Leila told me. Today, Aborigines are incarcerated at five times the rate of blacks in apartheid South Africa, and their death and suffering in custody is widespread.

In 2000, then NSW police minister Paul Whelan met Arthur and Leila in his office in Sydney and ordered a special investigation.

He promised them this ''would not be the end of the road''. There was no serious inquiry and the minister retired to his stud farm. He has returned none of my calls.

Leila could not read, yet this remarkable woman memorised almost every document and judgment. She died in 2004, broken-hearted. Incredibly, Arthur reached the age of 70 when many Aboriginal men are dead much earlier.

In a typical case this year, CCTV footage in Alice Springs police station showed a policewoman cleaning blood off the floor while a stricken Aboriginal man was left to die. Australia, said Prime Minister Julia Gillard on September 26, deserves a seat at the top table of the United Nations because it ''embraces the high ideals'' of the UN. No country since apartheid South Africa has been more condemned by the UN for its racism than Australia. When I last saw Arthur, we walked down to the Namoi riverbank and he told me how the police in Wee Waa were still frightened to go into the cell where Eddie had died and had pleaded with him to ''smoke out'' Eddie's spirit. ''No bloody way!'' Arthur told them. Peace to all their spirits; justice to all their people.

John Pilger is an award-winning journalist, author and documentary maker.

When I came to live in Australia in early 1978, having fled from the excesses of apartheid and police state South Africa, I knew that apartheid Australia was no better than what I had just left, but on a much smaller scale, because of the difference in numbers of the two indigenous populations.

After the Royal Commission into Deaths in Custody, there were hopes that there would be improvements, but these were idle hopes.

Steve Biko died in the back of a police van when the police moved a naked, unconscious, frozen Biko from Port Elizabeth to Pretoria, a distance of about 800km.

In West Australia an Aboriginal man boiled to death in the back of a police van - think privatised control - and what is the difference other than about 60 degrees Celsius?

The crime is just the same and the countries were/are just as apartheid-driven as ever they were - of course these days it is even worse in Australia than it has ever been because it is also practised on the asylum seekers.

Australia is an apartheid state no different from South Africa, Israel and many other countries around the world.

Civilisation and democracy are still a long way off - just look at the USA and the Trans-Pacific Partnership and all the other ills which are thrust upon us 99 percenters!

Weekend edition 24 APRIL 2013 CounterPunch :Australia's Racist Assault on Aboriginal People

Australia has again declared war on its Indigenous people, reminiscent of the brutality that brought universal condemnation on apartheid South Africa. Aboriginal people are to be driven from homelands where their communities have lived for thousands of years. In Western Australia, where mining companies make billion dollar profits exploiting Aboriginal land, the state government says it can no longer afford to “support” the homelands.

Vulnerable populations, already denied the basic services most Australians take for granted, are on notice of dispossession without consultation, and eviction at gunpoint. Yet again, Aboriginal leaders have warned of “a new generation of displaced people” and “cultural genocide”.

Genocide is a word Australians hate to hear. Genocide happens in other countries, not the “lucky” society that per capita is the second richest on earth. When “act of genocide” was used in the 1997 landmark report Bringing Them Home, which revealed that thousands of Indigenous children had been stolen from their communities by white institutions and systematically abused, a campaign of denial was launched by a far-right clique around the then prime minister John Howard. It included those who called themselves the Galatians Group, then Quadrant, then the Bennelong Society; the Murdoch press was their voice.

The Stolen Generation was exaggerated, they said, if it had happened at all. Colonial Australia was a benign place; there were no massacres. The First Australians were victims of their own cultural inferiority, or they were noble savages. Suitable euphemisms were deployed.

The government of the current prime minister, Tony Abbott, a conservative zealot, has revived this assault on a people who represent Australia’s singular uniqueness. Soon after coming to office, Abbott’s government cut $534 million in indigenous social programmes, including $160 million from the indigenous health budget and $13.4 million from indigenous legal aid.

In the 2014 report Overcoming Indigenous Disadvantage Key Indicators, the devastation is clear. The number of Aboriginal people hospitalised for self-harm has leapt, as have suicides among those as young as eleven. The indicators show a people impoverished, traumatised and abandoned. Read the classic expose of apartheid South Africa, The Discarded People by Cosmas Desmond, who told me he could write a similar account of Australia.

Having insulted indigenous Australians by declaring (at a G20 breakfast for David Cameron) that there was “nothing but bush” before the white man, Abbott announced that his government would no longer honour the longstanding commitment to Aboriginal homelands. He sneered, “It’s not the job of the taxpayers to subsidise lifestyle choices.”

The weapon used by Abbott and his redneck state and territorial counterparts is dispossession by abuse and propaganda, coercion and blackmail, such as his demand for a 99-year leasehold of Indigenous land in the Northern Territory in return for basic services: a land grab in all but name. The Minister for Indigenous Affairs, Nigel Scullion, refutes this, claiming “this is about communities and what communities want”. In fact, there has been no real consultation, only the co-option of a few.

Both conservative and Labor governments have already withdrawn the national jobs programme, CDEP, from the homelands, ending opportunities for employment, and prohibited investment in infrastructure: housing, generators, sanitation. The saving is peanuts.

The reason is an extreme doctrine that evokes the punitive campaigns of the early 20th century “chief protector of Aborigines”, such as the fanatic A.O. Neville who decreed that the first Australians “assimilate” to extinction. Influenced by the same eugenics movement that inspired the Nazis, Queensland’s “protection acts” were a model for South African apartheid. Today, the same dogma and racism are threaded through anthropology, politics, the bureaucracy and the media. “We are civilised, they are not,” wrote the acclaimed Australian historian Russel Ward two generations ago. The spirit is unchanged.

Having reported on Aboriginal communities since the 1960s, I have watched a seasonal routine whereby the Australian elite interrupts its “normal” mistreatment and neglect of the people of the First Nations, and attacks them outright. This happens when an election approaches, or a prime minister’s ratings are low. Kicking the blackfella is deemed popular, although grabbing minerals-rich land by stealth serves a more prosaic purpose. Driving people into the fringe slums of “economic hub towns” satisfies the social engineering urges of racists.

The last frontal attack was in 2007 when Prime Minister Howard sent the army into Aboriginal communities in the Northern Territory to “rescue children” who, said his minister for Aboriginal Affairs, Mal Brough, were being abused by paedophile gangs in “unthinkable numbers”.

Known as “the intervention”, the media played a vital role. In 2006, the national TV current affairs programme, the ABC’s Lateline, broadcast a sensational interview with a man whose face was concealed. Described as a “youth worker” who had lived in the Aboriginal community of Mutitjulu, he made a series of lurid allegations. Subsequently exposed as a senior government official who reported directly to the minister, his claims were discredited by the Australian Crime Commission, the Northern Territory Police and a damning report by child medical specialists. The community received no apology.

The 2007 “intervention” allowed the federal government to destroy many of the vestiges of self-determination in the Northern Territory, the only part of Australia where Aboriginal people had won federally-legislated land rights. Here, they had administered their homelands in ways with the dignity of self-determination and connection to land and culture and, as Amnesty reported, a 40 per cent lower mortality rate.

It is this “traditional life” that is anathema to a parasitic white industry of civil servants, contractors, lawyers and consultants that controls and often profits from Aboriginal Australia, if indirectly through the corporate structures imposed on Indigenous organisations. The homelands are seen as a threat, for they express a communalism at odds with the neo-conservatism that rules Australia. It is as if the enduring existence of a people who have survived and resisted more than two colonial centuries of massacre and theft remains a spectre on white Australia: a reminder of whose land this really is.

The current political attack was launched in the richest state, Western Australia. Last October, the state premier, Colin Barnett, announced that his government could not afford the $90 million budget for basic municipal services to 282 homelands: water, power, sanitation, schools, road maintenance, rubbish collection. It was the equivalent of informing the white suburbs of Perth that their lawn sprinklers would no longer sprinkle and their toilets no longer flush; and they had to move; and if they refused, the police would evict them.

Where would the dispossessed go? Where would they live? In six years, Barnett’s government has built few houses for Indigenous people in remote areas. In the Kimberley region, Indigenous homelessness — aside from natural disaster and civil strife — is one of the highest anywhere, in a state renowned for its conspicuous wealth, golf courses and prisons overflowing with impoverished black people. Western Australia jails Aboriginal males at more than eight times the rate of apartheid South Africa. It has one of the highest incarceration rates of juveniles in the world, almost all of them indigenous, including children kept in solitary confinement in adult prisons, with their mothers keeping vigil outside.

In 2013, the former prisons minister, Margaret Quirk, told me that the state was “racking and stacking” Aboriginal prisoners. When I asked what she meant, she said, “It’s warehousing.”

In March, Barnett changed his story. There was “emerging evidence”, he said, “of appalling mistreatment of little kids” in the homelands. What evidence? Barnett claimed that gonorrhoea had been found in children younger than 14, then conceded he did not know if these were in the homelands. His police commissioner, Karl O’Callaghan, chimed in that child sexual abuse was “rife”. He quoted a 15-year-old study by the Australian Institute of Family Studies. What he failed to say was that the report highlighted poverty as the overwhelming cause of “neglect” and that sexual abuse accounted for less than 10 per cent.

The Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, a federal agency, recently released a report on what it calls the “Fatal Burden” of Third World disease and trauma borne by Indigenous people “resulting in almost 100,000 years of life lost due to premature death”. This “fatal burden” is the product of extreme poverty imposed in Western Australia, as in the rest of Australia, by the denial of human rights.

In Barnett’s vast rich Western Australia, barely a fraction of mining, oil and gas revenue has benefited communities for which his government has a duty of care. In the town of Roeburne, in the midst of the booming minerals-rich Pilbara, 80 per cent of the indigenous children suffer from an ear infection called otitis media that causes deafness.

In 2011, the Barnett government displayed a brutality in the community of Oombulgurri the other homelands can expect. “First, the government closed the services,” wrote Tammy Solonec of Amnesty International, “It closed the shop, so people could not buy food and essentials. It closed the clinic, so the sick and the elderly had to move, and the school, so families with children had to leave, or face having their children taken away from them. The police station was the last service to close, then eventually the electricity and water were turned off. Finally, the ten residents who resolutely stayed to the end were forcibly evicted [leaving behind] personal possessions. [Then] the bulldozers rolled into Oombulgurri. The WA government has literally dug a hole and in it buried the rubble of people’s homes and personal belongings.”

In South Australia, the state and federal governments launched a similar attack on the 60 remote Indigenous communities. South Australia has a long-established Aboriginal Lands Trust, so people were able to defend their rights — up to a point. On 12 April, the federal government offered $15 million over five years. That such a miserly sum is considered enough to fund proper services in the great expanse of the state’s homelands is a measure of the value placed on Indigenous lives by white politicians who unhesitatingly spend $28 billion annually on armaments and the military. Haydn Bromley, chair of the Aboriginal Lands Trust told me, “The $15 million doesn’t include most of the homelands, and it will only cover bare essentials — power, water. Community development? Infrastructure? Forget it.”

The current distraction from these national dirty secrets is the approaching “celebrations” of the centenary of an Edwardian military disaster at Gallipoli in 1915 when 8,709 Australian and 2,779 New Zealand troops — the Anzacs — were sent to their death in a futile assault on a beach in Turkey. In recent years, governments in Canberra have promoted this imperial waste of life as an historical deity to mask the militarism that underpins Australia’s role as America’s “deputy sheriff” in the Pacific.

In bookshops, “Australian non-fiction” shelves are full of opportunistic tomes about wartime derring-do, heroes and jingoism. Suddenly, Aboriginal people who fought for the white man are fashionable, whereas those who fought against the white man in defence of their own country, Australia, are unfashionable. Indeed, they are officially non-people. The Australian War Memorial refuses to recognise their remarkable resistance to the British invasion. In a country littered with Anzac memorials, not one official memorial stands for the thousands of native Australians who fought and fell defending their homeland.

This is part of the “great Australian silence”, as W.E.H. Stanner in 1968 called his lecture in which he described a “cult of forgetfulness on a national scale”. He was referring to the Indigenous people. Today, the silence is ubiquitous. In Sydney, the Art Gallery of New South Wales currently has an exhibition, The Photograph and Australia, in which the timeline of this ancient country begins, incredibly, with Captain Cook.

The same silence covers another enduring, epic resistance. Extraordinary demonstrations of Indigenous women protesting the removal of their children and grandchildren by he state, some of them at gunpoint, are ignored by journalists and patronised by politicians. More Indigenous children are being wrenched from their homes and communities today than during the worst years of the Stolen Generation. A record 15,000 are presently detained “in care”; many are given to white families and will never return to their communities.

Last year, the West Australian Police Minister, Liza Harvey, attended a screening in Perth of my film, Utopia, which docmented the racism and thuggery of police towards black Australians, and the multiple deaths of young Aboriginal men in custody. The minister cried.

On her watch, 50 City of Perth armed police raided an Indigenous homeless camp at Matagarup, and drove off mostly elderly women and young mothers with children. The people in the camp described themselves as “refugees … seeking safety in our own country”. They called for the help of the United Nations High Commissioner on Refugees.

Australian politicians are nervous of the United Nations. Abbott’s response has been abuse. When Professor James Anaya, the UN Special Rapporteur on Indigenous People, described the racism of the “intervention” , Abbott told him to, “get a life” and “not listen to the old victim brigade”.

The planned closure of Indigenous homelands breaches Article 5 of the International Convention for the Elimination of Racial Discrimination (ICERD) and the Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous People (UNDRIP). Australia is committed to “provide effective mechanisms for prevention of, and redress for … any action which has the aim of dispossessing [Indigenous people] of their lands, territories or resources”. The Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights is blunt. “Forced evictions” are against the law.

An international momentum is building. In 2013, Pope Francis urged the world to act against racism and on behalf of “indigenous people who are increasingly isolated and abandoned”. It was South Africa’s defiance of such a basic principle of human rights that ignited the international opprobrium and campaign that brought down apartheid. Australia beware.

John Pilger can be reached through his website: johnpilger.com

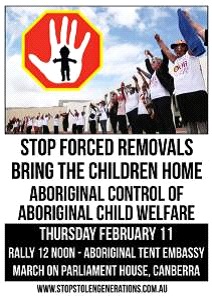

Join the Grandmothers Against Removals for a protest to mark the anniversary of the Apology to the Stolen Generations – sorry means you don’t do it again! We will be meeting at the Tent Embassy in Canberra until February 13 to discuss the road ahead for our struggle – please come and join us.

29 January 2016| GMAR Snap Protest at FACS| Strawberry Hills, SydneyThe recently formed GMAR Sydney group is targeting this FACS office for it’s ongoing role in the forced removals of Aboriginal children from their families. These removals and placements of children in out-of-home-care often breach policies, occur in the absence of support or engagement with families and without restoration plans. Abrupt “stealth” removals have become standard practice, creating intense trauma and dislocation for the children, families and community at large.

Founding member of the Sovereign Grannies group in Brisbane, Aunty Karen Fusi, is flying in to speak at the protest about the devastation child removals have caused her family and building the fight back. Friday’s protest will demand an immediate meeting with FACS management. Families will be heard!

Currently, there are more than 15,000 Aboriginal children in “out-of-home care” on any given night. This is more children than were forcibly removed at any point in Australian history. More than half of these children have not been placed back with their Aboriginal family, despite the “Aboriginal placement principle” being mandated by law in every State and Territory. There has also been a national push for changes in legislation that are seeing many more children removed until 18 years of age, with new “permanent guardianship” laws either planned or in place across Australia.

Stop the stolen generations and bring children the home!

Bring banners and placards. Spread the word!

GMAR is leading a conference at Matagarup, the Perth Tent Embassy from May 24 – May 30, to strategise for the future and to march on May 26 – Please share

On ‘Sorry Day’, May 26, the national network Grandmothers Against Removals (GMAR) will lead a protest in Perth against continuing Stolen Generations. This date marks 18 years since the release of the ‘Bringing Them Home’ report. This report detailed the horrors of the Stolen Generations of the 20th Century and called for urgent action to stop the continued removal of Aboriginal children from their families by ‘child protection’ agencies.

Since 1997 however, the number of Aboriginal children being forcibly removed has increased more than five times, with more than 15,000 Aboriginal kids in foster care today. In WA more than half of all children in ‘care’ are Aboriginal, despite being less than 5% of the population. This is an urgent national crises and affected families are fighting back. Grandmothers Against Removals stand as representatives of Sovereign Aboriginal Nations and fight for restoration of their sacred children to their people. Over the past 18 months the group has forced the issue into the national and international media spotlight, helped many families win their children back and forced negotiations with welfare departments in different states.

GMAR is appalled that WA Premier Colin Barnett is using “child protection” as an excuse to forcibly remove entire communities from their lands, recycling the same lies about child abuse used to justify the NT Intervention. These forced closures will be systematic child abuse on a massive scale, putting families into destitution, more kids into foster care, more adults into prison.

GMAR is leading a conference at Matagarup, the Perth Tent Embassy from May 24 – May 30, to strategise for the future and to march on May 26.

Western Australia has been chosen as a focus for the conference to show solidarity with communities facing closure and help build links between the struggles. Your support is vitally important to help us fight for the right of children to live with their families and the right of all Aboriginal people to live on their lands and determine their own futures.

Donations are urgently required to assist with the costs of travel, accommodation, food and other logistics for the conference. Please give generously and spread this message through your networks.

Donations can be made to:Today we march in protest against the unprecedented theft of Aboriginal children from their families by so-called “Child Protection” agencies across Australia.

We are in urgent need of protection from the criminal actions of these Departments, who persecute Aboriginal families and mobilise police to terrorise children with forced removals. More Aboriginal children are forcibly separated from their families at this moment than at any time in history.

We march in solidarity with the many Aboriginal families who suffer the fresh pain of forced removal every day. We march in solidarity with the black children who run away in fear from foster care placements and institutions every night.

We march to mark seven years since then Prime Minister Kevin Rudd made an “apology” to the Stolen Generations of the 20th Century, an apology loaded with the worst hypocrisy, given the crescendo of forced child removals that took place under the watch of his government.

There are currently more than 15,000 Aboriginal children in so-called “out of home care”. The majority of these removals are for alleged “neglect” – the exact rationale provided for tens of thousands of 20th Century removals. It is a term used to denigrate Aboriginal culture and the love and care provided by Aboriginal families and communities. It is a term that masks the systematic neglect of governments that enforce conditions of extreme poverty and social trauma on our communities. It is a term used to justify a continuing project of forced assimilation.

We march to demand recognition of the continuing Sovereignty of our nations and our fundamental right to determine our own future – we have been camping with the National Freedom Movement at the Aboriginal Tent Embassy for the last three weeks and support their manifesto.

We demand Aboriginal control of Aboriginal child welfare and a massive transfer of resources into Aboriginal hands to deal with unacceptable social conditions. We demand an end to the removals and a moratorium on the use of police armed with guns, batons and pepper spray to take children.

We demand a national restoration program to bring our children home. We have met with Nigel Scullion, Minister for Indigenous Affairs, who promised to work with us on this restoration program and an independent system that can monitor abuse from “Child Protection” – we will hold him to these promises and need to see immediate action in this regard.

There must be an end to the “mandatory reporting” system which creates a culture of fear and distrust with the schools, health and social services in our communities due an avalanche of reports from workers making racist assumptions about our families. Disgracefully, many of our own Aboriginal organisations are tied up in this reporting regime, enforced by funding agreements and draconian legislation.

We demand the full domestic implementation of the 1948 Genocide Convention into Australian law by repealing section 268.121 and 268.122 of the International Criminal Court (Consequential Amendments) Act 2002, in order to enable a challenge to the destruction of our religion, culture, bloodlines and communities by forced child removal and creating conditions of life set to destroy the group in whole or in part.

We appeal to all workers and organisations that have any contact with “Child Protection” to come out in support of our struggle. Our children are being taken out of schools, hospitals, playgrounds and homes across Australia. You MUST refuse to co-operate with this mass kidnapping of our children. You can help re-build the community controlled organisations that are needed to deal with any problems in our communities.

We call for international solidarity actions against the ongoing colonial oppression of Aboriginal people in Australia, as people fought Apartheid in South Africa – boycotts, sanctions and divestment. The Australian government commits troops to so called “peacekeeping” missions overseas, but we need an international volunteer force on the ground here to protect us from the ongoing war on our communities.

Our next day of action will be “National Sorry Day”, on May 26. We will mobilise again on Universal Children’s Day in October. We need people to join us in protests in your thousands. Workers from Aboriginal and child welfare organisations should stop work and show their solidarity with our struggle.

We will continue with our struggle until all of our babies are home.

Letter in The Age:

Regarding the tragic death of Ms Dhu, Anastasia Kanjere says the coroner recommended the police receive "cultural competency training", and that the footage of the incident shows she was "denied basic medical care" (Letters, 19/12). The police took Ms Dhu for medical assessment twice, and both times she was cleared by hospital doctors before being taken back to the police cells. The police alone should not be held responsible when the true nature of Ms Dhu's condition was undiagnosed.

Duncan Cameron, Parkdale

Article in the Sydney Morning Herald :

Boxing Day is the most important day on the Australian cricket calendar.

But if you ask most Australian cricket-lovers why this year's Boxing Day match is so significant, you'll receive a vacant look.

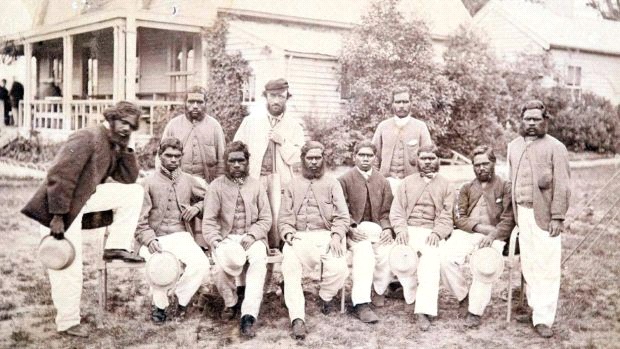

The Aboriginal team on Boxing Day, 1866, outside the MCG. The man at the back wearing a cap is Tom Wills. Photo: Supplied

The answer is that 150 years ago, something remarkable took place on Boxing Day at the MCG. It was a cricket match that was the consummation of a great drama in our national history – a drama of murder and healing.

On that Boxing Day, in 1866, an Aboriginal cricket team from the western district of Victoria played against the exclusive Melbourne Cricket Club. The black team was captained by a white man, Tom Wills – the greatest cricketer in the land.

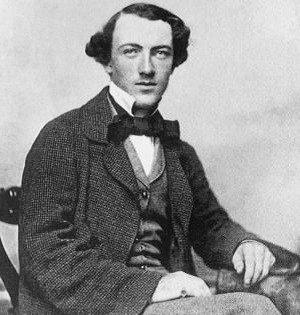

Tom Wills as a young man in 1857/58, when he was regarded as the finest cricketer in Australia. At roughly the same time he instigated the game of Australian Rules football. Photo: Terry Wills-Cooke

Born in NSW, Tom Wills descended from convicts. Growing up in western Victoria all his playmates were black. Tom grew up with the Djab Wurrung Aboriginal people and learnt their language and games until he was regarded as kin – a white boy in a sea of black faces.

As a young man Wills was the finest cricketer in Australia, his mind crammed with sporting genius. Along the way he crafted the first rules of what became Australian Rules football. But cricket was his game.

At the peak of his fame, in 1861, when 26 years old, something shattered his life. In that year he travelled with his father to central Queensland to settle a new pastoral property. There, on October 17, after lunch and in the heat of the day, local Kairi Aborigines attacked and slaughtered 19 white settlers.

Among the 19 dead lay Wills' father. It was the biggest killing of white settlers in Australian history. Miraculously, Wills survived.

As the blood coagulated on the dry grass, local white settlers sought revenge. The final death count has been lost in hysteria and time. But Wills did not kill anyone.

Marooned in Queensland, the forces of isolation, alcohol, and nightmares rendered his world unliveable. Wills' mind began to unravel.

In the shadow of his despair arose a remarkable story that led to the Boxing Day cricket match of 1866.

Returning to Victoria after the massacre, Tom travelled through the land where he had grown up as a boy among Aborigines. He helped find and then train 10 indigenous farm labourers. The son of man murdered by Aborigines helped create an Aboriginal cricket team. He became their white captain and coach.

He brought this team, whom the Melbourne media regarded as little more than "savages" to the MCG on Boxing Day to play the Melbourne Cricket Club. When Wills stepped on to the MCG leading his black team, 10,000 curious spectators craned their necks to observe the spectacle.

The word on the street was that Wills was mad, deranged. But what he did that day towers above what any Australian captain has ever done on the cricket field.

Some in the crowd whispered of his villainy, shaming his father's memory by playing with Aboriginal cricketers; to others he was a hero for building a bridge between black and white.

Wills spoke to his team in an Aboriginal tongue until, in the eyes of the Melbourne media, he was one of them.

Fearing humiliation, the ungracious Melbourne Cricket Club stacked its team with the best players it could unearth.

But public sympathy was with Wills and his team. As each wicket fell, the whispers in the crowd became a roar. The outsiders rode a wave of popularity.

Egalitarianism won the day. Aboriginal cricket was on everyone's lips. The black team lost the match but won the public's adulation.

Journalists ran about agog, astonished that this team tutored by the white Tom Wills could play so well. Unstated but implicit in every line was this: if they could play this English game of cricket, what else might they be capable of?

Just over a year later, that Aboriginal team prepared to go to England. It became our first-ever cricket team to tour England – 10 years before the first white Test team.

The 1866 Boxing Day Cricket Match was the denouement of one of the great, but little-known, chapters in Australian history.

How does a man, having lost his father in such a bloody fashion, find the courage and grace to create an Aboriginal cricket team? This is surely one of the great acts of healing in this nation's history.

But, sadly, I doubt whether there is a schoolboy or schoolgirl in Australia who could tell you this story.

How could this story – the nation's largest massacre of white settlers, the revenge attack upon Indigenous people, and the triumphant ascension on Boxing Day 1866 – be so little known?

The Boxing Day Test is the sporting heart of the nation. Nowhere else in this land do people assemble in such numbers to admire the gifted few.

This year we will watch in droves as Steve Smith and David Warner continue the tradition. Observers will experience the undiluted joy of sport, and, at times, its vulgar ostentation.

Millions will regurgitate memories of the Ashes, Bradman and Bodyline. I won't. I will think of something that happened 150 years ago, on this very day, in 1866.

When Tom Wills and his black team walked upon the MCG, just for an instant, cricket was an exalted game, suspended above a yet-to-emerge nation and spoke to us of what it might mean to be Australian.

Greg de Moore is conjoint associate professor of Psychiatry at University of Western Sydney and author of Tom Wills: First Wild Man of Australian Sport.

Article in the Sydney Morning Herald :

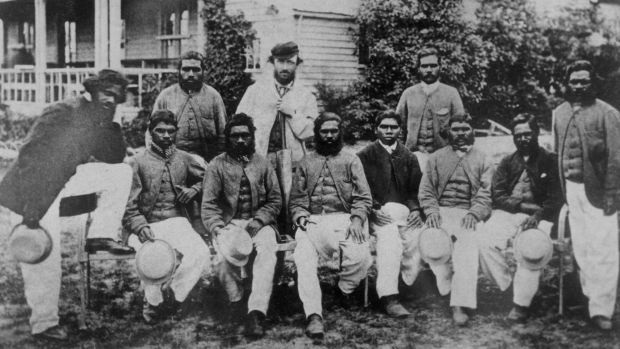

It's the greatest team photo in Australian sporting history. Usually said to have been taken at the MCG on Boxing Day 1866, some claim it was taken in Sydney two months later. But this is the small end of the discussion.

Look at the faces – they have seen a lot. This includes the whitefella, team captain Tom Wills. Plenty of people nowadays think they know Tom, but I'm not sure he's all that knowable. His life is a sequence of experiences that simply do not happen today, one of them being that he lived through the phase of Australian history known as "first contact". In the early 1840s he played with Tjapwurrung kids at Moyston, outside Ararat, speaking their language.

Members of the team that played at the MCG on Boxing Day in 1866 and later went on tour. Photo: Supplied

Statistics in this historical area are hard to get, but the population of the Aboriginal tribes on the edge of Melbourne fell 90 per cent in 20 years. In 1858, eight years before this photo was taken, David Syme's Melbourne Age solemnly declared that its readers had a Christian duty to help "smooth the pillow of a dying race".

This is ostensibly a cricket photo, but the Aboriginal players in this picture, all from western Victoria, had seen dispossession, disease and murder at a catastrophic rate. Like photographs of Truganinni taken around the same time in Tasmania, these are people witnessing the end of a world. Their world.

One reason for the big crowd at the 1866 Boxing Day match was that many Melburnians took the opportunity to see a race of people thought to be soon extinct.

Johnny Mullagh, whose Aboriginal name was later printed by an English newspaper as Unaarrimin, is the slight, upstanding figure standing to Wills' right (as you face the photo). He appears to have been a world-class talent, topping the averages in both batting and bowling on the tour of England two years later. Hired for a time as a professional by the Melbourne Cricket Club, he ended up living and dying by a waterhole outside Harrow in western Victoria, alone but for his dogs and the daguerreotype of a white woman he met on the tour of England. Tragic story? This is tragedy on a Shakespearean scale, only its scope extends beyond any one individual.

On the tour of England, Mullagh refused to take the field in York after the Aboriginal players were excluded from the lunch tent. In later years, one story goes that after the captain of Apsley called Mullagh a nigger while he was batting he hit that individual a catch next ball and walked from the field to show that the spirit of a game can be killed. (There is an alternative version of this story; there is an alternative version of virtually all these stories.)

In 1861, five years before the Boxing Day photo was taken, Tom Wills' father and 19 others died near Emerald in Queensland in the biggest massacre of whites by blacks in Australian history. Tom Wills was lucky to miss the slaughter. He then lived for two years in a war zone in which both sides killed men, women and children but one side was much more lethal militarily. Wills was left with an impossible split in his psyche.

During the Boxing Day match at the MCG, when one of the Aboriginal players, Jellico, was asked if Wills was teaching him to read and write, he replied: "What use Wills? He too much along of us. He speak nothing now but blackfella talk."

But who is Jellico? The white records usually claim he is the youngish man seated on the left. He had, I believe, two brothers in the team – Tarpot, standing to Wills' left, and Dick-a-Dick, standing on the far right. Only Dick-a-Dick's great grandson, the late Jack Kennedy from Dimboola, insisted that the player identified as Jellico was actually Dick-a-Dick.

In 1864, two years before the Boxing Day photo was taken, Dick-a-Dick found three children lost in the bush for nine days north-west of Horsham.

Thereafter, he was for a time called King Richard. His Aboriginal name was later given in an English newspaper as Jungunjinanuke. Through Jack Kennedy I got a more likely spelling – Djungadjinganook.

On the 1868 tour he would stand with a thin defensive shield used for deflecting spears in tribal warfare, inviting young men – sometimes groups of young men – to hit him with cricket balls from 15 paces. He got hit only once and said that was when he wasn't looking. Old Jack Kennedy took me to the graveyard where Dick-a-Dick lies at the now disused Ebenezer Mission, outside Dimboola. There are two Rose brothers in the picture – King Cole (also known as Charlie Rose), with his foot on the chair, and Harry Rose, seated third from the right.

Their descendant, Lionel Rose, was bantamweight champion of the world in the 1960s. King Cole died in England on the cricket tour. It has been written that a number of his teammates were depressed thereafter. The ultimate terror for a traditional Aboriginal person is to die outside their "country", away from the company of their ancestral spirits, thereby condemning their spirit to forever wander alone.

The 1866 Boxing Day match was followed by a tour of eastern Australia. In the course of the tour and a few months thereafter, four Aboriginal players died. A number of players passed through the Aboriginal team; three of those who died are not in this photo, but Jellico, the fourth fatality, is.

Trooper Kennedy at Lake Wallace (now called Edenhope), where the 1866-67 tour started and ended, wrote that some members of the team "were continually drunk". Wills, by this time, was an alcoholic – what part did he play in the drinking? In the purchase of alcohol? Dick-a-Dick tried to make a stand, administering tribal punishments like nulla nulla beatings for drunkeness.

And here is an irony of history – Dick-a-Dick gave one of his sons to Trooper Kennedy to bring up, the policeman from Lake Wallace who wrote about drunkeness being prevalent in the Aboriginal team. That's why Dick-a-Dick's great grandson was called Jack Kennedy.

After Wills gruesomely committed suicide in 1880, stabbing himself in the heart, his name dropped out of polite conversation and then out of memory in white society. But in western Victoria, Jack Kennedy heard about Tom Wills as a child. "He died of the drink," he told me. The Aboriginal players on the 1868 tour of England never got paid. Old Jack told me they got dropped in Sydney and "had to make their own way home".

The other player I know something about is James Cuzens (also Couzens or Cousins), the last seated figure on the right. Only 155 centimetres in height, he was, for that time, a genuinely fast bowler. His descendant, Warrnambool artist Fiona Clarke, has done the poster for the 2016 Boxing Day match.

Her grandfather, Uncle Banjo Clarke, was one of the great human beings it has been my good fortune to meet. He had traditional Aboriginal beliefs but gave his religion to those who asked as Baha'i.

These are just some of the stories I know. There would be plenty more. What other Australian team photo has the winds of history rushing through it as strongly as this one?

About 5 years ago WorkSafe Victoria moved out of its 2-storey building at the corner of Plenty Road and Bell Street in Preston, a suburb north east of the city of Melbourne. About 2 years ago it started being occupied, but it was more recently that what was painted on the outside gave information about who occupied the building and what it was being used for.

The address is 238-250 Plenty Road, Preston, Vic 3072

Here are some of the photos which show the painting on the building:

Their aim was Community Centre to make decisions of their own But it was more than just a meeting place For many it was home

(This is on the Bell Street side of the building)

Many years ago some Elders decided That their people needed a meeting place Where they would come and be united.

(This is on the Plenty Road side of the building)

The following letter appeared in The Age newspaper on 22 AUGUST 2019:

How can Victoria's First Nations have any faith in the Andrews Government's treaty negotiations when they treat traditional owners such as the Djab Wurrung so flippantly. 'We'll arrest you if you don't shut up' or words to that effect.

After more than two years seeking a mutually acceptable route change for the planned duplication of the Western Highway into a freeway, the Andrews government has told the Djab Wurrung there will be no change to the road route.

The freeway will destroy sacred cultural sites and hundreds of tall eucalypt trees to save a few minutes' driving time between Melbourne and Adelaide. Some of these trees may be 800 years old. They are Djab Wurrung birthing trees and connect culture and language with the natural environment. Once cut down, they cannot be retrieved except in the memories of the old people. It's an appalling situation and needs better understanding by the government.

Ken Lovett, Preston

Convincing Ground - Learning to fall in love with your country - by Bruce Pascoe, published by Aboriginal Studies Press, 2007

"Pascoe draws on the past through a critical examination of major historical works and witness accounts and finds uncanny parallels between the techniques and language used there to today's national political stage. He has written Convincing Ground for all Australians, as an antidote to the great Australian inability to deal respectfully with the nation's constructed indigenous past.

For Pascoe, the Australian character was not forged at Gallipoli, Eureka and the back of Bourke, but in the furnace of Murderous Flat, Convincing Ground and Werribee. He knows we can't reverse the past, but believes we can bring in our soul from the fog of delusion. Pascoe proposes a way forward, beyond shady intellectual argument and immature nationalism, with our strengths enhanced and our weaknesses acknowledged and addressed." (from the back cover of the book)

Bruce Pascoe is a widely published and award-winning writer, editor and anthologist, whose books include Shark, Ruby-eyed Coucal, Earth and Nightjar.

North of Capricorn - The Untold Story of Australia's North by Henry Reynolds, published by Allen and Unwin, 2003

The Wik Case - Issues and Implications edited by Graham Hiley, Published by Butterworths, 1997

Mannie De Saxe also has a personal web site, which may be found by clicking on the link: RED JOS: HUMAN RIGHTS ACTIVISM

Mannie's blogs may be accessed by clicking on to the following links:

MannieBlog (from 1 August 2003 to 31 December 2005)

Activist Kicks Backs - Blognow archive re-housed - 2005-2009

RED JOS BLOGSPOT (from January 2009 onwards)

This page was created on 25 NOVEMBER 2011 and updated 23 AUGUST 2019

PAGE 75