The gay community has had much to grieve in the age of AIDS and has found many ways to express their sadness and celebrate the legacy of lost lives. Kerry Bashford looks at the rituals we practise in an effort to remember and heal – from funerals to personal memorials and public gatherings of grief. Photos by Garrie Maguire

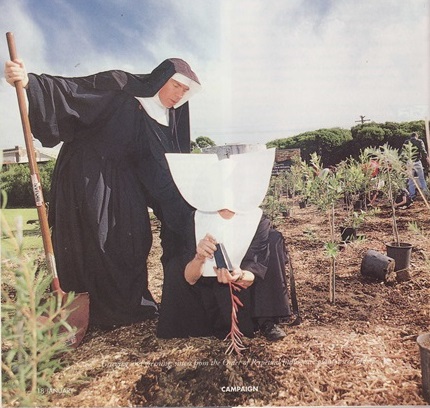

A pair of nuns with stubble on their faces and shovels in their hands turn the earth and plant a sapling in the forbidding soil of an inner city park. A middle-aged mother lights a candle from the outstretched hand of a pierced and spiky haired dyke. In a warehouse by the water, friends and family unfold the fabric that bares an achingly personal account of a life that continues to touch them long months and years after their loss.

The rituals that remind us of departed loved ones have become as essential parts of gay life as the celebrations that defy the impact of their loss on our lives. They can be cryptic ceremonies, indecipherable to anyone outside a social circle, or common gestures that have found poignancy in popular culture. Irrespective of whether you wear a personal memento or wrap yourself in red ribbons, these rituals of loss help us to heal and interpret the tragedy as much as they represent a brazen effort to maintain a memory in the face of insurmountable grief.

If our lives express our distance from mainstream culture, our deaths make the gulf of experience and expectations painfully clear. The ceremony that stands for a funeral, it seems, anticipates the death of an elderly person or a family member. In the traditional funeral, there is little room for the outsider and little place for any personal ritual.

Any sector of the funeral industry that has dealt with the HIV/AIDS communities must have recognised a more than subtle subversion of the ceremony in the last ten years of the health crisis. With 20 years’ experience, Robert Peel of Value Funerals in Sydney has noticed a trend by which gays or people with HIV/AIDS have rewritten some of the rules. Our funerals “tend to be more organised” and more thought is put into personalising the event to the extent of several people writing up the service themselves. Apart from staging, even the tone can be markedly different. David Ashton of Mannings Funerals has discovered that “most of the gay community take funerals as a farewell, not a sad event for mourning.”

With a lack of symbols relevant to our grief or sense of loss, both the deceased and their survivors tend to invent their own icons to be displayed at the ceremony or buried or cremated along with the coffin. Ashton suggests, “A lot of different things are involved in gay funerals (like) requests for different coloured caskets…. With rainbow colours or balloons hanging from the back of the hearse,” or as Peel recalls, “white blooms thrown into the air… There are no set patterns regarding funerals. Funerals are what you want them to be.” (The well known White Ladies Funerals, for instance, once arranged a ceremony that stripped the occasion of any of its solemnity. Things proceeded as usual until the coffin slid behind the crematorium curtain. The mourners were alarmed to see the coffin reappear until the facilitator explained. The deceased had been an actor and refused to pass from their sight without one last curtain call. He received a standing ovation.)

These idiosyncrasies and innovations do not always sit well with families of the deceased, especially those estranged or only coming to terms with their relative being gay, let alone dying from AIDS. They can feel resentment towards the lovers and friends who they see as responsible for their loved one’s lifestyle and death. Others make brave attempts to reconcile themselves to their relative’s wishes. At worst, the family, without clear directives from the deceased, can take over a funeral, leaving the ceremony a strange and foreign affair that fails to express the true nature of the person.

Therefore it is important to understand the protocol of funerals, explained by David Ashton. “When we arrange a funeral, we take it up with the one person from the first call, whether it’s a partner or the mother or the father of the deceased….. We do get a number of people saying, ‘Oh, I want it done this way.’ Well, we just don’t listen to that and we carry it out how the arranger wants it.” As Robert Peel suggests, “It’s very important for the person to leave a will and to leave a partner, for instance, as the executor,” with living wills best accommodating the desires of the deceased for a ceremony that suits their sensibilities.

Long after a loved one has passed away, continuing memorials can articulate our despair or make some sense of the separation we have experienced. These gestures give a framework to our grief and serve as an acknowledgment of the ongoing loss felt by survivors.

Tom is a librarian from Melbourne who lost his lover of ten years, Peter, two years ago. Peter’s ashes went to Tasmania where Peter was born. At first he resented the decision and the tyranny of distance that forbade him from regularly visiting his lover’s last site of rest. But he remembered that he’d “saved the flowers from the funeral that made a substantial potpourri on my study shelf. I started sprinkling the potpourri at places that were meaningful to us both – our backyard, a holiday campsite, a park. I even threw a few handfuls at the PLWHAs marching at Mardi Gras”.

On the anniversary of his lover’s death, Tom felt that he needed a ceremony but found it too much pressure to organise an appropriate event. He held a tea party for his closest friends and as they were leaving he gave them each envelopes of the precious petals to distribute in places meaningful to them. He has kept the last remaining slivers in a pouch that hangs from a discreet and simple shrine in the hallway.

Realising that the demands of a memorial ritual could put undue pressure on survivors trying to get on with their lives, Darren, who died at 33, left helpful instructions as to how he wanted his carried out. When his sister was contacted by his solicitor shortly after his passing, she had no idea that she had been appointed Mistress of Ceremonies for an event to be held a year after his death. All the instructions sealed in an envelope seemed simple until the last entry that asked her to provide substances for the memorial soiree with a helpful list of Darren’s dealers and a substantial budget to ensure that all the mourners would be satisfied. “I didn’t know what to do. I’d never had anything more than an aspirin in my life but I went ahead with his request anyway. I had a series of very strange but kind of sweet encounters with all these strangers who sent me off with little bags of speed, ecstasies and marijuana. I don’t know why he chose me to do his shopping for him. I think it was one last joke at my expense.”

Paula is a lesbian teacher now living in Lismore who found that her ongoing memorial ceremonies for her girlfriend Jan were necessary not only for her grieving but also as instruction to lesbian culture, ambivalent on the subject of AIDS and not as used to dealing with loss as their gay male counterparts. “I found that my lesbian friends were almost as dismissive of my grief or uncomfortable with it as relatives who could not really comprehend our relationship to begin with. I’ve held private little gatherings not only to remember Janet and process my grief but also to illustrate to them the depth of my loss.”

Other memorials have been practised to prove a point but not always with such serious intent. There’s the story of the American drag queen who organised her own service with a rather wicked twist. She made her remaining sisters pledge that they would appear each year at her graveside in the most fabulous drag imaginable. But the promise didn’t stop there. The diva had been reunited in death with her estranged relatives with whom she shared the family plot. She had the visitors remind them of her presence by sprinkling glitter over their graves.

Rarely has grief been as ritually and publicly acknowledged as it has throughout the AIDS crisis. Since the early 80s, annual events have made powerful expressions of a community in mourning. These events help galvanise the grieving, as well as acknowledge the breathtaking scope of the crisis and the many lives it has affected and apprehended.

It’s hard to imagine a more hopeful expression of remembering than an AIDS memorial grove slowly springing from the barren earth. In an inner city park, an area left derelict by its former use as a garbage dump and brickworks is being transformed by an affecting attempt to come to terms with loss and desolation.

Mannie De Saxe has been co-ordinating the planting of trees in Sydney Park near Newtown since May, 1994 after eighteen months of negotiating with the local council and waiting for the poisoned earth to become fertile again. After caring for his first CSN (Community Support Network) client over a long period, he thought, “there are other ways of remembering people who have died”. Observing some original plantings in Washington and local initiatives in the Blue Mountains west of Sydney, De Saxe quickly noted that trees were an excellent token of remembrance as “people believe they are living organisms... A tree is a living memory and it’s been used as a memorial system for a very long time.”

What distinguishes a tree planting from any other gesture of commemoration is that results can continue long after the ritual has brought the person to some kind of resolution. It is visible long after a candle has been extinguished, or a fabric folded away. Also, it is a public, yet intimate act. One thing that De Saxe has noticed is that the AIDS memorial grove has attracted people who might find other public events too confronting or inaccessible. “People feel they can do their grieving in a private sort of a way. It’s an emotional outlet for someone to dig a hole and plant a tree.”

With the assistance of Ken Lovett, who has faithfully recorded the names of those who have participated or been remembered, five weekends have seen the placing of some 2000 trees. As De Saxe explains, “Some have planted more than one tree or they’ve planted one tree as a group thing.” Plantings will recommence later this year around March, according to the seasons.

While tree planting will enable memorials to grow and be visited for years to come, the practice of quilting has brought together sometimes estranged survivors while ensuring that the message of loss can reach the wider community. The Quilt is perhaps the most portable of AIDS emblems (outside of the red ribbon), allowing every major city to attempt annual events and for the Quilt to tour the country areas, as it did in every region of New South Wales over December (1995).

Originally launched by Ita Buttrose on World AIDS Day 1988, the Quilt now encompasses 98 blocks and 1700 individual people have been remembered. Barry Edwards is the convenor of the Sydney Branch and has watched the way that the process of constructing a panel can bring together survivors and help them sort through some of their grief through the simple act of stitching.

This is perhaps because the process is so personalised. As every queen knows, there is no limit to how one can accessorise. This has seen the Quilt evolve from a simple register of names to a rich tapestry of eclectic textures and remarkable materials, from pink tulle to an entire leather block. As Edwards points out, “At first a lot (of the panels) had single names so you couldn’t identify them and now people are putting on the whole name and the year of birth…. (Now) there are kids’ blocks that often have little paintings. People put in photographs, personal things like combs to make it even more individual… There’s lots of teddy bears, two or three sewn on, lots of rainbow flags and pink triangles.”

A testament to the Quilt’s capacity to document lost lives and serve as a poignant reminder of the progress of the AIDS crisis is that “both of the founders now have panels, Andrew Carter and Richard Johnson, which really makes you think when people who’ve made panels become the subject of one themselves.”

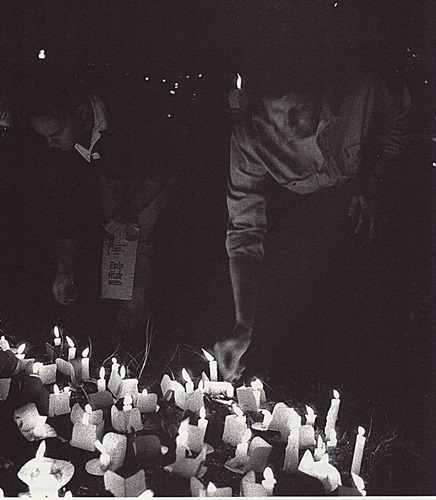

Certainly the growth of the community affected by HIV/AIDS is best expressed by the yearly growth in attendance at the Candlelight Rallies held around the country in May each year. The procession and the reading of the names that follows has made the rally the most significant memorial ceremony in this country outside of ANZAC Day, an analogy that would not be lost on many survivors.

Candlelight is a communal outpouring of grief and the most palpable evidence of the weight of the loss. Catherine McGettigan, convenor of the last two Sydney events has concluded, “One of the main reasons (for its popularity) is that it is a way to express grief in a supportive atmosphere where you’re not entrapped by religious rituals. It’s also a public way of showing how AIDS has affected the community and an expression of the number of people we have lost. It’s also a time where you can say farewells and regather and keep fighting and supporting.”

The impact of the ceremony is not lost on the convenor even though she has worked on the event for a number of years as volunteer and employee. “I remember last year standing at the top of the street and turning round and seeing just a sea of candles and I could not see the end. That was just an overwhelming feeling that every one of those candles represented a life affected by AIDS. How could anybody not realise how significant those effects were and how much grief and sadness we’re all feeling?”

McGettigan believes that the growing numbers “will probably continue for years to come.” But what of the years to come if and when the crisis comes to a conclusion and no more lives need to be lost? “There will always be a place for a ritual to remember the people who have died. Although the crisis may be over, the effects of those deaths on those who have continued will continue for the rest of their lives and it will be a reminder to generations to come that this happened.”

Timothy Conigrave, Rob Lake, David Edler and Aldo Spina at an ACT UP rally in Sydney. Photo: POSITIVE LIFE NSW

Australia’s first AIDS-related death was in Melbourne in July 1983. Not only has the world changed considerably since then but the shape of activism has changed too. This thirtieth anniversary is an opportunity to look back on the history of HIV activism and consider its future.

The people who gathered together in the early and mid- 1980s were part of a much less connected world. Their information came from overseas contacts, travel and gay publications. From 1982 onwards, overseas sources suggested that gay men were suffering mysterious symptoms of compromised immune systems. Growing numbers of men were being diagnosed with the previously rare form of cancer, Kaposi’s sarcoma, and other devastating opportunistic infections.

When HIV first reached Australia, activism was centred on AIDS Councils, which formed very quickly. These organisations were not exclusively gay and lesbian but their membership came from this community. The Victorian AIDS Action Committee (now the Victorian AIDS Council) met for the first time at Melbourne’s Laird Hotel in July 1983. Similar AIDS Councils were established in Queensland, South Australia, Western Australia, Tasmania, NSW and the ACT between 1983 and 1985. The Australian Federation of AIDS Organisations (AFAO), founded in 1985, served as a national umbrella organisation. These community-based organisations drew heavily from New York and San Francisco models.

Individuals from a wide range of backgrounds, including some marginalised groups, joined together to work with bureaucratic structures to formulate a response to HIV in Australia in the 1980s. Many of those dealing with the toll of the epidemic had been poorly treated by both government agencies and medical authorities in the past.

The Australian response to HIV in the 1980s has justifiably received much international acclaim. Many of those who remember the early years of the AIDS epidemic reflect on the way that AIDS Councils were staffed by volunteers. In an oral history interview held by the National Library of Australia, academic and writer Dennis Altman describes the individuals who led these Councils as ‘heroes’. The federal government was largely supportive of these organisations and was prepared to empower individuals to educate others about HIV.

During the 1980s and 1990s, office bearers in AIDS Councils, alongside community volunteers including many who were living with HIV, manned telephones and gave talks to organisations such as Lifeline and state and regional health services. Members of the heterosexual community, including some women whose sons had been affected by HIV, also gave time and energy as volunteers. There are numerous accounts of people across Australia doing what they could to assist, including bringing pots of soup into the headquarters of the Queensland AIDS Committee or spending days and nights caring for and nursing people dying of AIDS-related illnesses.

Ken, who was living with HIV in Brisbane in 1985, volunteered with the Queensland AIDS Council in that year.

He told The Courier Mail that he was getting valuable support from the organisation, felt he was playing a supportive role to others and was, in turn, receiving friendship and feeling less isolated.

HIV activism in the 1980s focused on very practical concerns. The medical profession was still learning about the virus so the earliest activism in Australia centred on making information about HIV available and supporting those who were directly affected. Many of those who lived through these years describe the difficulties of losing friends and lovers, while attempting to manage their own health and educate others.

Despite living through a time many liken to a war in terms of the loss of lives, many HIV activists remember the 1980s as a time when a community pulled together. David Menadue explains that ‘the desperation of the times (the eighties) meant more hands were needed on deck to do things that governments had often not funded HIV organisations to do.

‘HIV organisations depended on volunteer workforces and community involvement was high. People wanted to help and that included rattling the cages of government when they weren’t listening to the needs of people who were dying or providing resources to communities-at-risk to try to stop new infections.’

Although Australian activists generally had a better relationship with the federal government than activists in the United States, tensions became more obvious as the epidemic continued. People who were living with HIV became increasingly concerned that their needs and concerns were not being voiced.

A very significant event for HIV activism occurred with the formation of the National Association of People With HIV Australia. The organisation can trace its origins to the 1988 national AIDS conference in Tasmania, when, during the closing plenary, 20 activists took to the stage and demanded that HIV positive people be represented in the AIDS response.

It was the first time in Australia that a group of people stood up and self-identified as HIV positive. This action led to the establishment of the National People Living with AIDS Coalition (NPLWAC) – an advocacy organisation with the primary mission of increasing positive representation on a national level and which was later to become NAPWHA.

One of the major points of contention between Australian activists and government focused on access to HIV medications such as AZT. This medication was initially thought to slow the frequency and severity of AIDS-associated opportunistic infections.

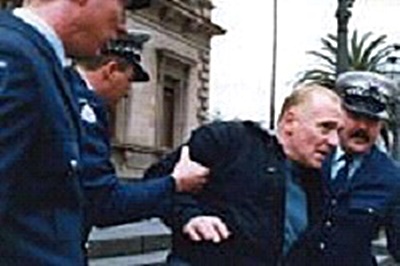

In 1990, the tension between AIDS activists and government erupted when protestors interrupted a speech by Federal Health Minister Brian Howe at the National AIDS Conference, demanding that the process of approving experimental HIV medications such as AZT be fast-tracked.

At that point AZT was given only to people with T-cell counts below 200. This contrasted with the US and Canada, where people living with HIV had access to the medication before they became sick. In Australia, people living with HIV were particularly concerned that access to medication was proving difficult and that HIV positive people were not being given more agency in the process of medical treatment.

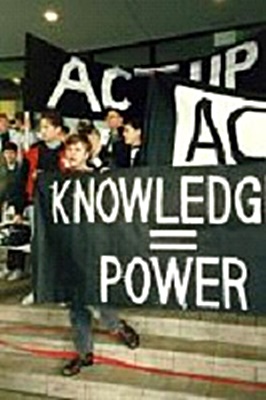

The American activist group ACT UP, which had been formed by Larry Kramer in 1987, addressed the concerns of many Australian activists and particularly those of people living with HIV. On 10 April 1990, more than 80 people met to form a Sydney ACT UP chapter. A number of people involved with this first meeting had attended an emergency drug meeting that had been called by People Living With AIDS (PLWA) NSW to discuss a lack of treatment and to urge the formation of ACT UP. Members of other marginalised groups, including sex workers, were also part of this activism.

The first Sydney ACT UP protest involved more than 50 members who demonstrated at the federal health department, targeting the Australian Drug Evaluation Committee, which was responsible for drug licensing and for AZT only being available for people with CD4 counts of 200 or fewer. Other chapters of ACT UP were launched in Melbourne, Brisbane, Canberra and Perth before the end of 1990.

ACT UP was highly active across Australia in the early 1990s, with a range of protests, actions and zaps that varied in size and impact. One of ACT UP’s major campaigns took place on 6 June 1991, designated ‘D Day’. It was to draw attention to delays in the approval process for medication needed by people living with HIV. On this date, a series of coordinated protests took place across Australia.

In the early morning, members of Melbourne ACT UP removed the flowers from the Melbourne Floral Clock, replacing them with white crosses. In Canberra, members of ACT UP held a candlelight vigil, stitched a memorial quilt panel and, most spectacularly, blew whistles in the House of Representatives, while two men jumped over the Public Gallery balcony into the chamber. Geoffrey Harrison, who was involved in the Canberra actions, recalls, ‘it was pretty amazing to see’ Parliament stopped. Collectively, the ‘D Day’ actions did generate considerable media attention both nationally and internationally and as Harrison remembers, ‘put our message out to other people’.

ACT UP also drew attention to other issues, such as the treatment in the media of people living with HIV. In one press release from 14 August 1991, Sydney ACT UP asserted that ‘with a few outstanding exceptions, the Australian media has had a shameful record of reporting on HIV and AIDS issues . . . People Living with HIV and AIDS in Australia are daily insulted and disenfranchised by the media’s common use of terms such as “AIDS victim”, “AIDS carrier”, “AIDS-contaminated blood” and worst of all, “innocent victims”‘.

Throughout its most active period, ACT UP in Australia maintained strong links with the state-based AIDS councils and with activists who worked within bureaucratic structures. Many were involved in both AIDS councils and in ACT UP. Lloyd Grosse remembers using the office facilities of the AIDS Council of NSW to produce some work for ACT UP. In a notable campaign from 1991, members of ACT UP in Melbourne worked with members of the Victorian AIDS Council to protest the threatened closure of the Fairfield Hospital, which had particular expertise in HIV treatment.

By 1993 it became clear that the type of activism practised by ACT UP was in decline.

Emotional exhaustion had taken a toll on many members. Others had been affected by ill-health or had died. The 1991 Baume Report had appeared to address many of the concerns ACT UP held about the approvals process and access to medication for people living with HIV. The development of new anti-retroviral drugs in 1994 and 1995 also provided new hope and changed the focus of AIDS activism in Australia. Finally, ACT UP in the US, which had provided a level of inspiration and a model to be adapted in an Australian context, was also on the wane.

Ironically, the success of ACT UP in achieving respect and inclusion for people living with HIV meant there was no longer a need for the organisation. Once people living with HIV had fought successfully for their inclusion and empowerment in the medical treatment process, the need for ACT UP receded.

Two of the most important shifts in HIV activism have occurred relatively recently. In 1994 and 1995, there was a significant breakthrough with the success of combination therapies, which greatly extended the life expectancies of many people. The remarkable growth of the internet since the 1990s has also changed the way people organise and support each other.

Some people criticise the state of activism in modern Australia, arguing that the country has become something of a ‘slacktivist nation’. Perhaps it is fairer to note that activism is still powerful but that its modus operandi has shifted. Many who were involved with AIDS councils, ACT UP or people living with HIV organisations in the late 1980s now use the internet for communication and support. Both Geoffrey Harrison, who was very involved with ACT UP in Melbourne, and Lloyd Grosse, who was involved with the AIDS Council of NSW and ACT UP, view the internet as a positive way of organising, maintaining contact with friends from the past and reducing isolation.

David Menadue believes that activism is alive and well in Australia today. ‘If you accept that activism can be done within effective government-funded community structures.

‘If you believe that true activism occurs when groups are completely independent of government and largely involves rallies and street protests, we are certainly failing on that score. I prefer the robustness of government-funded HIV organisations that have built up respect from governments and are able to push boundaries with them about the necessity to get effective messages across to affected communities.’

The history of HIV activism in Australia is a remarkable one. It is a story of a marginalised group of people working closely with the federal government to achieved better outcomes for themselves and others affected by HIV. Activism has ebbed and flowed.

The initial years of the HIV epidemic saw a mass voluntary effort that deserves to be remembered. In 1988, the formation of the National People Living with AIDS Coalition (as NAPWHA was then known) gave HIV positive people a forum in which to make their concerns and voices heard. By the 1990s, these voices were steering activism in a powerful and innovative direction. ACT UP offered a way in which to express their concerns and to lobby. More recently, advances in treatment options for people living with HIV and the internet have shifted the scope of activism. But it is clear Australia’s world-leading response has been driven by extraordinary individuals living through incredibly challenging times.

Additional photos, from top:

D-Day protesters at Flinders Street Station on 6 June 1991 when members of ACT UP staged radical protests across the country, using the letter ‘D’ to represent the words deaths, drugs, delays and deadline. Photo: Australian Lesbian and Gay ArchivesDr Shirleene Robinson is a Vice Chancellor's Innovation Fellow in Modern history at Macquarie University. Her current research focuses on HIV and volunteerism in Australian history. She wishes to thank Ross Duffin, Lloyd Grosse, Geoffrey Harrison and David Menadue for their generosity in sharing their experiences with her in 2012 and 2013.

"All of the 97 Australian AIDS Memorial Quilts we have acquired are now on line and can be viewed here

Australian AIDS Memorial Quilts

The Museum's fabulous team of volunteers have also been documenting (as much as we can ) information on the individual panels and are up to Quilt 88 so by early next year (2014) the panel information will be up in detail.

I also developed an exhibition last year HIV & AIDS 30 years on: the Australian story

HIV and AIDS 30 years on: the Australian story

| Photos

of the Groves |

Mannie has a personal web site: RED JOS: HUMAN RIGHTS ACTIVISM

Mannie's blogs may be accessed by clicking on to the following links:

MannieBlog (from 1 August 2003 to 31 December 2005)

Activist Kicks Backs - Blognow archive re-housed - 2005-2009

RED JOS BLOGSPOT (from January 2009 onwards)

This page created on 14 AUGUST 2013 and updated 8 MAY 2017

PAGE 172