Dinner for Debbie Brennan, Easter (15 April) 1990 at Kim's Restaurant, Darlinghurst, Sydney

From left: Ken Lovett, Mannie De Saxe, Johanna Traynor, PeterMcGregor, Alison Thorne

PHOTO: Debbie Brennan

Peter McGregor died in Sydney on 11 January 2008. He was just 60 years old.

Peter was an activist from before the 1970s and in 1971 was one of those, with Meredith Burgmann. who actively attempted to disrupt the Springbok rugby tour of Australia.

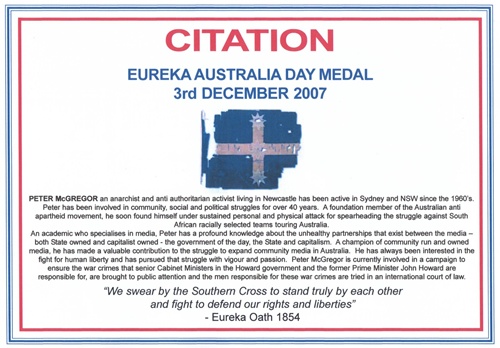

Peter was in Melbourne only a few weeks ago to go to Ballarat to receive a Eureka award for his attempted citizen's arrest of Philip Ruddock at the University of New South Wales, and his attempted citizen's arrest of John Howard, Philip Ruddock and Alexander Downer at Parliament House in Canberra during 2007.

In his 40 years of activism Peter was always, as an Anarcho groupie, a friend of gays and lesbians, working with them to achieve equality and end discrimination.

In fact, Peter was a friend of activists of all sorts and political persuasions, and he had an enormous circle of friends.

Peter at gleebooks on 20 February 1997, launching his books "versions of freedom" and "visions of freedom"

PHOTO: Mannie De Saxe

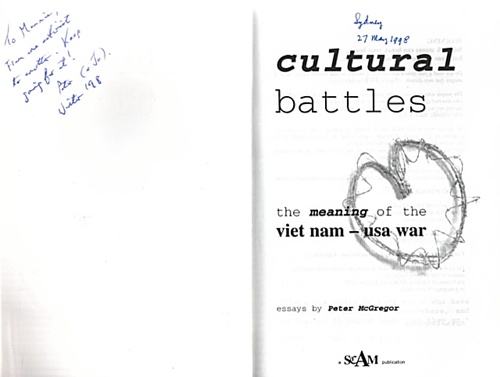

The above inscription in Peter's 1998 book on Vietnam is a typical "PeterMac" statement

One of Peter's regular activities was to visit the SPAIDS Groves on tree-planting days whenever he could get to Sydney from Newcastle. He also brought friends with him on regular occasions, and amongst the friends were John and Margaret Brink, two anti-apartheid South African activists who had had to leave South Africa in the 1960s for political reasons. Peter became very friendly with them and they influenced him in his anti-apartheid activism for many years.

PHOTO: Ken Lovett

Peter and his partner Jo have lived in Newcastle for many years, and he leaves his partner Jo, family and many, many friends around Australia and overseas who will remember him with great warmth and sorrow at his early death.

This message has been posted by Ken Lovett and Mannie De Saxe, Lesbian and Gay Solidarity, Melbourne, and long time friends of Peter's and Jo's.

Peter became the meat in the sandwich and was ultimately destroyed by two of Sydney’s universities, one in the east, and one in the west.

The story of Peter and the university in the east, known as the University of New South Wales (the word university is very questionable under the circumstances!) is now very well known to most of us, although we believe the story is not yet over. Some of us will continue to pursue the issue until there is some sort of resolution from this institute which has become a toady of the late unlamented Howard government, politically and economically.

I have sent them an email in response to one of the last ones Peter received before his untimely death. Here are both of them:

Mannie De Saxe, Lesbian and Gay Solidarity, Melbourne

PO Box 1675

Preston South

Vic 3072

The fact that Peter McGregor died on 11 January 2008 does not mean that the matter between him and the University is now closed.

More than ever, it is necessary for the University to demonstrate that it is not a university in name only, but that the meaning of the word university is still understood to be that of an institution which upholds the traditions of a seat of learning.

The University, the Gilbert and Tobin Centre, the Law Faculty and the people involved in the events leading to the arrest of Peter McGregor need to make public apologies which are placed in the media in prominent positions so that the community is made aware of the injustices of the actions taken to have Peter McGregor arrested and ignominiously thrown out of the University.

Until such time as this is done, the matter will not be laid to rest. Justice must not only be done, it must be seen to be done.

Mannie De Saxe, Lesbian and Gay Solidarity, Melbourne.

d.caddies@unsw.edu.au, k.oneile@unsw.edu.augtcentre@unsw.edu.augeorge.williams@unsw.edu.au

Subject: Your email to the Vice-Chancellor From: "Victoria Finlay"

Dear Mr McGregor,

I am responding to your email to the Vice-Chancellor. I understand that the police prosecution has been withdrawn. The University regards the matter as closed and will not respond to any further correspondence regarding the matter.

Yours sincerely,The university in the west, which was the institution where Peter was employed until his untimely retirement because of circumstances too numerous to mention, and which Peter attacked with all the forces he could muster, is the University of Western Sydney.

Peter kept us informed about his attempts to stop the university – another misnomer under the circumstances – from destroying the faculty in which he worked and the courses which had become so successful in media and communications – courses which in these days of dishonesty by the media and control by the media bosses are more than ever needed.

Economic rationalism of the Howard era put paid to these courses – the university decided they could not attract enough finance and students to make the courses – in their terms – viable. So the courses had to go, and Peter with them! He could not bear to stay at an institution which had made his work and position untenable.

Peter wrote a comprehensive document, titled:

(with so much happening in my own school, concerning the implementation of these changes, & without an open, university-wide discussion informing us what’s happening in other Schools/Colleges, it’s hard to know what’s happening beyond my School. Hence I welcome similar responses by staff - & students – from other Schools.)

(Peter’s complete document is too lengthy to be included here, but I have a copy of it, and it can be copied by anyone interested in taking up the ongoing fight on Peter’s behalf.)

While I was doing a post-graduate degree between 1993 and 1996 at the University of Western Sydney, Nepean, as that part of UWS was then called, the current vice chancellor Professor Maling was sacked from her position. There was a big outcry and I joined in the outrage which had been committed by the university. Peter was part of the Nepean unit and we had a great deal of contact at that time over the issue.

The outcome of the sacking, and what had led up to it, was the amalgamation of the three main units of UWS at that time, Nepean, Macarthur and Hawkesbury into a university with one name, University of Western Sydney.So the three separate identities, which had historical educational significance, were lost in the interests of economic rationalism. John Howard’s coming to government in 1996 ensured the ongoing politicization of the privatisation of university education in Australia.

In keeping with Peter’s ongoing involvement with the gay, lesbian, transgender and HIV/AIDS communities, when a homophobic forum was held at the Bankstown campus of UWS in 2002/3 involving a fundamentalist Muslim psychology lecturer at UWS at which there were as guest lecturers prominent members of the fundamentalist sections of the Muslim community to discuss homosexuality and the ‘criminality’ thereof, Peter joined with us in our protests at the outrage being committed by a member of the university staff and involving gay, lesbian and transgender students. The lecturer was suspended at the time while an inquiry was held as to the circumstances of the forum, but ultimately the involvement with the vice-chancellor who was the same one involved with Peter over the dismantling of his faculty, was not to everyone’s satisfaction.

This was yet another example of Peter’s involvement with the widest range of issues involving injustice, prejudice, discrimination and abuse in all political spheres in which Peter McGregor was involved for most of his adult life. There are too few like Peter in this world, and that, in the end, was what Peter seems not to have been able to take any longer – apart from his failing health, about which he was all to well aware.

Peter will be sadly missed by so many of us, but we would be failing in our activist duties if we did not persevere with all the causes which were close to Peter’s heart. In this we hope that Peter’s partner of so many years, Johanna Trainor, will take some heart! We offer her all the support possible of which we are able, now and in the future.

Mannie De Saxe, Lesbian and Gay Solidarity, Melbourne, 23 January 2008

Obituary for Peter McGregor in the Sydney Morning Herald:

PETER McGREGOR, activist, academic, and writer, was one of the Australian left's most committed and energetic sons. He was involved with - and sometimes led - many of the most significant campaigns of the past 40 years; against apartheid and the Vietnam war, for the rights of Aboriginal Australians, asylum seekers and David Hicks, about climate change and censorship.

The campaigns were often unpopular when McGregor took them up. Yet history has come down on his side more often than not. Perhaps his biggest coup was the cancellation of a tour to Australia by a South African cricket team. McGregor and Meredith Burgmann, co-convenors of the Anti-Apartheid Movement with Denis Freney, wrote to Sir Donald Bradman, urging that Australians not play a team chosen on a racial basis. After lengthy correspondence, Bradman called the tour off. Bradman's son, John, said later that the correspondence had convinced his father to act.

Peter James McGregor, who has died at 60, grew up in Roseville. His father left home when he was young, leaving Alice McGregor, her boys Ken and Peter, and her sister May with limited income in a comfortable suburb. Peter was dux of Roseville primary school, attended North Sydney Boys High School, graduated from Sydney University and taught maths at Manly High.

Alice and Peter were early supporters of the campaign to free Nelson Mandela from prison. At Sydney University from 1965, McGregor's interest in apartheid grew. He met South African exiles in Sydney, including John and Margaret Brink; John had been jailed after the Sharpeville massacre in 1960.

After falling out with school heads for attending a protest meeting, McGregor left teaching and devoted most of his time in the early 1970s to the Australian Anti-Apartheid Movement. The group fought against the South African rugby tour of Australia in 1971, protested over the appearance of a whites-only lifesaving team at Bondi, gathered assistance for South African political prisoners and played the key role against the cricket tour.

The nature and method of creating social change was instrumental to Peter's thinking. The Vietnam war was a major cause for him and he visited the country several times, later publishing Cultural Battles: The Meaning Of The Vietnam-USA War (1998).

He became an anarchist in 1973 and, more recently, joined the Socialist Alliance. His libertarian and anarchistic leanings were formed by the counter-culture and unlike many contemporaries who found professional complacency, he maintained the rage. With little stomach for compromise or patience for the finesse of institutional politics, he worked tirelessly for radical causes. He was arrested (many times) and charged (several times).He found that protesting alone did not necessarily bring social change. Anarchism came with personal cost and drove him to some compromises. He bought a house in Leichhardt with his partner, Johanna Trainor; after further study, at the University of NSW, he became a lecturer in media studies at Macquarie University and at the University of Western Sydney, from 1987 to 2004. He took his commitment to political movements more seriously than his career. His students found him inspiring.

The protesting continued. He campaigned to free Tim Anderson, Paul Alister and Ross Dunn over the Ananda Marga conspiracy case and Anderson over the Hilton bombing. Their convictions were finally overturned. He campaigned against the Labor council in Leichhardt, over Aboriginal deaths in custody and for East Timor.

Only last year he tried to make a citizen's arrest of Philip Ruddock, then Attorney-General, for alleged war crimes.

He supported anyone who lampooned the big end of town. He attended the launch in 1999 of a new satirical newspaper, The Chaser, published by a group of students to whom he had lent support. The newspaper led to the TV series, The Chaser's War on Everything.McGregor couldn't win them all, of course. He taught film studies. Mumbling his displeasure over a film in a city cinema, he finally stood up and announced to the audience that this was a reactionary and distasteful spectacle and he proposed to walk out. He suggested they all do the same. Only one person, his sheepish companion, followed.He was kind, warm, generous, self-deprecating, an eloquent raconteur and free of the brooding resentment towards political foes that often encumbers radical outsiders. He wrote recently of activism: "But there aren't enough of us, and we aren't getting there. While, as Alice Walker says 'activism is my rent for living on this planet', I'm getting more and more behind on that rent."

Yet a week before he died he was selling copies of Green Left Weekly on street corners in Newcastle, where he lived. Three days before his death, he drove to Sydney to support a protest at the US consulate on the sixth anniversary of Guantanamo Bay jail.

Despite his busy mind and body, Peter McGregor had dementia; his future was bleak. He chose to take his own life.

It was a last act of activism. He is survived by Johanna Trainor, his companion of 28 years, brother Ken and cousins David and John.

By Tony Stephens

Death has taken from us an extraordinary peace activist, internationalist, Left thinker, and comrade: Peter McGregor. He died on 11 January after a protracted illness, throughout which he continued major political work. Peter combined an infectious optimism that a truly free and equal society is possible with an unshakable commitment to popular activism, tempered by respect for self-determination and creativity. He believed in the radicalisation of human society in line with anarcho-syndicalist principles, more compatible with revolutionary socialism than is often understood. His high-profile contribution to the nascent anti-racist and anti-war movements in 1960s Australia, public advocacy for civil liberties, enduring solidarity with Third World liberation struggles and humble but distinguished co-leadership of the Anti-Apartheid Movement into the early 1970s framed his later trajectory.

Those privileged to work with Peter during the victorious Anti-Apartheid campaign in 1971, whatever our interpretative differences, can only but recall an efficient, press-savvy organiser, alert to the political diversity of a genuine mass movement and frenetically determined to keep us focussed on the endgame: a permanent ban on racially-selected sporting teams touring Australia. This itself was part of a broader strategy to isolate the white-minority regime in South Africa and compel it to embrace multiracial democracy. In my own role as a leader of that movement on Sydney University campus, Peter was an indispensable guide, subtly chiding my naive adventurism but rock-solid when confrontation with the state emerged. Once, as a racially-selected life-saving team began its 1971 tour—an Afrikaner stunt from “Whites Only” beaches—we organised a march from campus down Cleveland Street to Surf House in Surry Hills with minimal notice, drawing several hundred students, led solemnly by pallbearers with a black coffin to symbolise the death of equality in sport. Shortly after, we both had a hand in the ill-fated plan whereby a young pig was to be disguised as a baby, greased, anaesthetised and smuggled into the Sydney Cricket Ground for release during a Springbok-Australia rugby match. A police bust in the early hours of the morning of the match disrupted the plan, and the pig—codenamed “Longbottom” in deference to a reviled Sydney superintendent known for harassing student mobilisations—was last seen escaping down a Glebe lane with varied neighbours in hot pursuit.

The Australian Nazi Party, ideologically aligned with apartheid, organised a brutal and cowardly assault on McGregor in 1971 which I witnessed. Its propagator, one Ross Lesley May (aka “The Skull”), subsequently served time; but the police more often than not acquiesced in Nazi violence and that of fellow racists and the more fanatical rugby fans, who were often inseparable. As systematic police violence against the indigenous population before, during and after anti-apartheid’s summit has shown, racism is endemic to the colonial mentality. The declaration of a state of emergency by premier Bjelke-Petersen in Queensland meant that the police state would save the Nazis extra resources in the North. Unlike seasoned campaigners, myself and other students had been stunned when assaulted by uniformed Nazis at Sydney airport whilst there to peacefully protest the arrival of the all-white South African life-saving team. Even the traditionally-racist Sydney Daily Telegraph was momentarily shocked; in its lead article, moreover (see 24 March 1971). Sir Frank Packer’s media empire was better known for its racist editorials, some secretly penned by the poet Kenneth Slessor, according to his widow. As an aside, arrest during the Anti Apartheid Movement mobilisations—with or without conviction—was still a pretext for exclusion from practice as a teacher in Queensland as recently as 2003.

Peter McGregor encapsulated the link between commitment to daily activism and long-term goals which led the movement to flourish. Nationally, collective organisation was shared with Zimbabwean Sekai Holland, engineer Jim Holland, academics like Meredith Burgmann and Dan O’Neill, South African exiles John and Margaret Brink, lawyers like Peter Tobin (tragically killed in a 1977 air crash in Cuba), aboriginal leaders like Gary Foley, Sam Watson, Dennis Walker and Donald Brady, as well as student organisations, progressive church leaders and the Left political parties. This was a formidable and diverse leadership of which to be part, yet McGregor had wide critical support and respect. He was an accomplished pamphleteer, learned and quick-witted in public speeches, adept at involving newcomers, and at the same time dedicated to the endless hours of meetings, mundane chores and planning required to keep the struggle coherent and dynamic. Much of this would later serve his academic career as a lecturer in communications at the University of Western Sydney, 1987-2004.

McGregor’s intellectual work during this ensuing, rich period saw much of his considerable energy dedicated to teaching and research on hegemonic media and the corporate takeover of public space and social communication. He prepared students to better understand what went on “behind the news”. Colleagues remember his democratic pedagogy, humour, and constant challenge to “the dominant paradigm”. He organised a major conference with Noam Chomsky during his Australian visit in the early 1990s. His book Cultural Battles: The meaning of the Vietnam - USA war (1998) remains an important tool for Media & Communication Studies. During a complex period of neocon university re-(read de)structuring, McGregor was a front-line activist for the National Tertiary Education Union.

Moreover, the “love and rage”—a favourite signature—continued into retirement. When Left activists and public intellectuals turned away in droves from the proposition “Be reasonable: demand the impossible!”, Peter sought new and creative ways to fight an increasingly ruthless, war-oriented ruling class, joining the Socialist Alliance soon after its formation early in the new millennium. An Australia-East Timor Association comrade and former UWS colleague recalls his “unrestrained support for numerous Australian and international solidarity movements with Third World Liberation struggles ... Indigenous Australians, East Timor, West Papua, Central and South America”.

In a letter to major media outlets in late 2006, McGregor pointed out that Howard’s media reforms had allowed Australian richest man, another Packer, to “virtually double his money overnight ... the media magnates have never had it so good.” The Packer group, he speculated, would repay Howard at the next election. This letter, written in catchy journalese, shows acute comprehension of the relation between major corporations and the capitalist state, oiled by the sycophancy of the major parties. And the outcome? “A welfare state for the rich.” The letter also promoted an event he co-organised, a free speech trial under the banner of the “Kerry Packer Dis-Memorial protest”, in honour of Howard's taxpayer-funded memorial “for one of the nation’s most renowned tax cheats.” The letter concludes, as Phillip Adams had protested, that “Australia did a lot for Kerry but he didn’t do much for Australia” (The Weekend Australian, 18 February 2006). The arrests which followed at the Dis-Memorial event were, said Adams, a “symptom of Australia’s arrested development …(justifying) a memorial service for free speech, a state funeral for democracy.”

Splendidly if not consciously, however, McGregor saved some of his best for last. At a forum on the ever-more-fashionable “War on Terror” organised by the Gilbert & Tobin Law Centre at the University of NSW in July 2007, he protested from the floor against the presence of attorney-general Phillip Ruddock, during the latter’s speech. This is an all-but-universally recognised right for delegates. Moreover, McGregor’s intention had been to serve Ruddock with a citizen’s arrest warrant for, in sum, crimes against humanity, with the warrant also applicable to PM Howard and other ministers. The politician in question, it will be recalled, co-authored some of the most draconian legislation against civil liberties yet seen in Australia, ably supported by some government-funded academics at the conference, and by the Labor Party.

But university authorities, Ruddock’s bodyguard and state police ejected McGregor from the conference, and he was promptly charged, in effect, with trespass. Thus were two elements of the protest joined, with exquisite clarity. The first highlighted the hypocritical and bellicose agenda of the bi-partisan “War on Terror”, via legitimate citizen’s intervention . The second showed to graphic effect the links between significant sectors of our pseudo-public universities (the “academic war machine”), the material reality of intervention in the Middle East (massive carnage and social destruction for imperial oil domination), and the ideological role of the police and “security forces” in everyday Australian life. For a single protest by a team of one, this is surely a reasonable achievement by any standards. And more followed.

After some academics and journalists at the conference questioned McGregor’s ejection, and scores of protests were sent to the vice chancellor and conference organisers over subsequent weeks, the charges were dropped. Indeed the university eventually went to some lengths to appear as though it had no responsibility in the matter. Widespread solidarity, together with McGregor’s persistence and unselfish commitment to principle, had led to a humiliating backdown. Given that some academics involved, such as George Williams, director of the Gilbert & Tobin Law Centre, have previously spoken out against the systematic erosion of civil liberties, it would seem consistent that the university now publishes a statement, however belated, unreservedly apologising for its actions, acknowledging McGregor’s critical contribution to the conference, and affirming that it will in future respect the right to protest as basic to Australian society.

In turbulent times, ideas must flourish. Peter McGregor’s war on obscenity, disarming humility and, in his own words, “love and rage” for humanity will long be remembered. To quote another distinguished activist and labour historian, Rowan Cahill: “His 'crime' was to maintain the link between leftist principles and rage, and to imagine anything was possible, all of which have become crimes in today's political toady-land.”

Postscript: Peter’s partner has suggested that anyone wanting to make a donation in his memory select from organisations he supported: Community Aid Abroad, Oxfam, MMIETS (Mary MacKillop Institute for East Timorese Studies), AETA (Australia East Timor Association), Australia West Papua Association, Boomerang Project, APHEDA, the Fred Hollows Foundation, Doctors without Borders, Swords Into Ploughshares, Green Left Weekly, the Indigenous Social Justice Association, or Justice Action.

Robert Austin Robert Austin web link

See also: Gay, Lesbian, Transgender, HIV (GLTH) Asylum Seekers - Part 1

See also: Gay, Lesbian, Transgender, HIV (GLTH) Asylum Seekers - Part 2

See also: Gay, Lesbian, Transgender, HIV (GLTH) Asylum Seekers - Part 3