(Abbreviation: Sydney Star Observer = SSO)

Taking us back to the hate crimes of the 70s, 80s, 90s and beyond has produced two articles in recent days which have provided some missing links and information and hopefully will produce proper investigations so that the 30 or more GLTH murders will have the murderers apprehended for crimes for which they have walked free for the last 20 or 30 years or more.

There are two reports in this post - one from the Sydney Morning Herald from early August 2013, and the other from the Sydney Star Observer a week later covering much the same information, but providing more publicity to Sydney's and New South Wales' police force shame in not bothering to solve at least 30 of the gay murders during the 70s, 80s and 90s because of their ongoing homophobia and disinterest.

Two boys play cards at the Keelong detention centre, south of Wollongong, in April 1991. "Tell me some good stories, you cunt," says one.

"About fag-bashing?" asks the other. And this 17-year-old inmate does not disappoint. "It was heaps fun," he says. With sadistic relish, he regales his fellow prisoner, and another at Sydney's Minda Detention Centre a few months later, with his reminiscences.

He reckons he was 12 when he started. He talks about hunting in packs of as many as 30 youths who would ambush homosexual men and punch and kick them and stomp on their heads, from Alexandria Park to Kings Cross and Centennial Park to Bondi and Tamarama. They'd go "cliff-jumping" and push gays over the edge. "Ah! Help, help!" he mocks one victim. "Heaps funny. Used to love how they scream, eh?"

The headlines are his trophies. "Got heaps of clippings at home, man, from all the poofters that we bashed."

"You're a sick puppy, mate." says his new friend at Keelong.

"It's a sport in Redfern ... it's a fuckin' hobby, mate. 'What are you doin' tonight, boys? Oh, just goin' fag-bashin.' "

He does not realise, but both his friends are wearing listening devices. He is in custody because he killed a man. He and seven of his mates. They will become known as the Alexandria Eight.

On January 15, 1990, after a game of basketball, they lured 33-year-old Richard Johnson to a toilet block in inner-city Alexandria Park. It was one of Sydney's many gay beats, a place for men to meet for casual and anonymous sex. Johnson had left his phone number on the wall. The gang - aged 16 to 18, most of them students or former students from nearby Cleveland Street High, a couple from a Catholic school - called the number to "bait the poofter". Johnson took the bait and they bashed him to death.

Behind bars, a couple of the youthful killers start naming names, suggesting who among the Alexandria Eight - and who among their extended network of schoolmates and associates - may have committed other gay bashings and murders. One of the eight, Ronald Morgan, skites about an attack at Bondi. "I had me new 'Boks from America on that day, too.

I had all blood over 'em … He should have went off the cliff that night but he didn't … We went down and put a cigarette butt out on his head."Also wearing a listening device is Dean Barry Howard, another of the eight. He is helping the cops now, but that doesn't stop him complaining. "I wish I would've done more to that fuckin' Johnson bloke if I'm gunna get 10 years. Two kicks and I'm gunna fuckin' get 10 years for it - five years for each kick."

Howard, in fact, is sentenced to eight years for murder, the reduction partly a reward for assisting police. In his own callous arithmetic: four years for each kick.

Detective sergeant Steve McCann had planted those bugs while the eight teenagers awaited sentences for manslaughter and murder. The homicide investigator was the first in the NSW police force to explore potential links between this case and a succession of murders and savage assaults of gay men, from the inner city to the Bondi cliff-tops. Some of his colleagues called him "the gay avenger". It wasn't meant kindly. McCann was straight, for the record, and simply determined to throw light on some unsolved crimes. They included the bashing murder of martial arts expert Raymond Keam, 43, in Randwick's Alison Park, also a gay beat, in January 1987; the killing of 50-year-old schoolteacher William Allen in Alexandria Park on December 28, 1988, a little over a year before the killing of Johnson in the same location; and the death of Cleveland Street High teacher Wayne Tonks in his Artarmon unit on May 19, 1990.

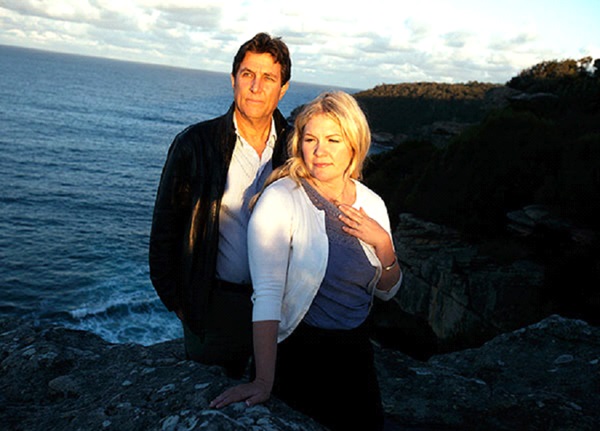

Working with McCann was Sue Thompson, a lawyer and former state ombudsman's investigator who had joined the force in January 1990 to co-ordinate its liaison with the gay and lesbian community. McCann and Thompson soon realised this blood sport called poofter-bashing was consuming many more "sick puppies" than the Alexandria Eight. They would encounter the Tamarama Three and the Bondi Boys, a local gang of about 30 which, despite its name, included girls, said to cheer on the head-kickers.

Thompson would write research papers, attain international recognition and be awarded the Police Medal in recognition of her 12 years in the pioneering gay liaison role. Using police data, she found 46 gay-hate murders in NSW between 1989 and 1999. Criminologist Stephen Tomsen backed those numbers with his 2002 finding of about 50 gay-hate murders between 1985 and 1995.

Their startling figures, while noted by the experts, never captured the public's attention. They were quite an understatement, in any case. They accounted only for reported homicides. They did not include cases filed away as suicides, deaths by misadventure or disappearances.

From bitter experience, Thompson now knows that at least some of those, and possibly many, were murders. Today she can count about 80 deaths or disappearances, mainly in Sydney but some in regional NSW, dating from the late 1970s to late 1990s - all potentially fitting this category of gay-hate crime. Of those, 30 remain unsolved.

********************************

While a "wave" of gay-hate murders was widely reported, Thompson says: "It was never just a wave. It is much more accurate to describe it as an epidemic." (Curiously, Melbourne police and media have never reported a culture of antigay violence of these proportions.)

Thompson's list includes some much-publicised cases, notably that of the brilliant young American mathematician Scott Johnson - no relation to Richard Johnson - whose naked body was found at the base of a 50-metre cliff on the Manly side of North Head, near Blue Fish Point, on December 9, 1988. A coroner soon agreed with police and declared it a suicide.

Johnson's brother Steve never believed it. In 2007, from Boston, he launched his own investigation. Unlike most families, he had the means. Steve Johnson is an internet entrepreneur who made his fortune by creating an algorithm that made it possible to deliver pictures over phone lines, the earliest form of digital "streaming media". He hired Daniel Glick, a former Newsweek investigative journalist, to travel to Sydney. "Pretty much on day one," says Glick, "it became clear that the place where Scott died was a gay beat." Police had told the coroner otherwise. But gay men came here, took off their clothes, sunbaked and hoped to get lucky.

"At least some police knew about this at the time," says Glick. Scott Johnson, 27, was gay. He was about to be awarded his PhD at the Australian National University in Canberra. Glick again: "Gay men don't go to gay beats to commit suicide. Period."

In June 2012, 23 years after Scott's death, deputy state coroner Carmel Forbes threw out the suicide finding. She considered the weight of the research amassed by Steve Johnson, with a team that included Sue Thompson, and found it could have been a gay-hate murder or an accident. Police announced a $100,000 reward in the case in February - the day after the ABC's Australian Story featured the family's battle.

"At first, I was focused only on Scott's death," says Johnson. "Then we started hearing from other families and other men who had survived vicious assaults around the time Scott died. I was shocked to learn how many gay men had died ... there were hundreds, possibly thousands, of assaults against gay men during this era.

"There was a culture of gay-hate bashings ... It didn't stop at the Harbour Bridge. We've heard stories of the equivalent of the Alexandria Eight or the Bondi Boys who regularly gay-bashed along the northern beaches."

The postcodes for the unpublicised cases stretch from Mosman to Collaroy on the north side. There were the brothers from Narrabeen, aged 15 and 12, who would travel to the city in the late 1980s to bash and rob gays and Asians in Kings Cross and Moore Park. A couple of cases involve men found naked at the base of cliffs, north and south of the harbour, their clothes folded on the cliff-tops - as with Scott Johnson.

Importantly, to qualify for this "gay-hate" category, the victims need not have been homosexual. It was a question of the motive. Might the killers have mistaken them for being gay? The bigger question is whether it is really possible that Sydney experienced a gay-hate murder epidemic and nobody much noticed. To answer that, we need to consider the era.

Sydney's first Gay Mardi Gras parade in 1978 coincided roughly with the first of the murders on Thompson's list. And just as thousands of gays and lesbians were emboldened to come out, the world's first case of AIDS was diagnosed in 1981. In those days, it was a death sentence. Many saw gay men as walking vectors of a killer disease. Only in 1984 did NSW decriminalise homosexuality.

"A lot of cops didn't get the memo," says Glick. He reports the question a policeman asked Marguerite O'Connell, the sister of Scott Johnson's boyfriend and the last person to see Scott alive: "Did you know your brother was a poofter?" And then: "Do you still love him?"

Gays didn't trust police, so commonly failed to report assaults. The prevailing police attitude, says Thompson, was "if they're gay or lesbian and a victim of crime, they asked for it". There was no internet, no Grindr or Gaymatchmaker - the social network could be a public toilet. In 1987 came the Grim Reaper commercial. In a bowling alley, the Reaper skittled tenpins in the forms of men, women and children. The ad was hailed for its success in terrifying Australians into safer sex, but it left an unintended, indelible message for some: the Reaper was a "poofter".

"Those lads have a lot to answer for," argues Steve Page, the cop who exposed the many failings of his colleagues on gay-hate crimes. Today, Page heads security for a major corporation but he was a detective sergeant in homicide when he took over Steve McCann's files in 2000 and launched Operation Taradale. Page and McCann's work uncovered extensive networks of youths who were either involved themselves or clearly knew who was. When they denied and denied, however, it was not enough to meet the tests of admissible evidence and reasonable doubt. The Alexandria Eight, who have long done their time - terms of between four and a half years and 10 years - have been charged with no other gay-hate crimes. In January 2002, Page re-interviewed the storyteller from Keelong.

Now he reckoned he had been "skylarking" and boasting, while admitting, "I'd say some of it happened" and adding "I'm sure we never pushed anyone off a cliff that didn't get back up".

But the dozens of kids in those gangs have grown up. They are approaching middle-age. Not all did the bashing but they have been living with these secrets, and the guilt, ever since. "Someone's going to open their mouth one day," says Ted Russell, whose 31-year-old son John was found at the base of a Bondi cliff in November, 1989.

******************************************

Sue Thompson accompanies Steve Page to Marks Park on the headland that separates Bondi and Tamarama, where the former colleagues give Good Weekend a tour of this one-time killing field. In the 1980s and '90s it was widely known as a gay beat where men met in the bushes and the honeycomb caverns surrounding the coastal walkway. We stand at a cliff-top lookout on Mackenzies Point, with views north to Bondi Beach and south to Tamarama. Page points towards Bondi, to a lower cliff edge. "John Russell was found on the rocks below that point." Page turns towards Tamarama and points to a ledge four metres away. "Kritchikorn went over there."

About 3am on July 21, 1990, Kritchikorn Rattanajurathaporn, a 34-year-old Thai national, found company at this lookout. As he and the friendly stranger chatted, three teenagers approached.

Brothers David and Sean McAuliffe and Matthew Davis had set out from Redfern, after a session of booze and bongs, with a plan to "roll a poof". Sean McAuliffe came with a claw hammer. They beat the other man unconscious and battered Kritchikorn. In his bid to flee, Davis would say, Kritchikorn stumbled backwards over the cliff. The Tamarama Three would be sentenced to 20 years for his murder but have been found guilty of no other gay-hate crime.

We stroll for less than two minutes towards Tamarama. Page points to a rock shelf. "They found Ross Warren's car keys about there." Warren, a gay 25-year-old television newsreader from Wollongong, parked his car on the western fringe of Marks Park early on the morning of July 22, 1989. He hasn't been seen since.

In his short-sleeved business shirt, Page still looks like a burly cop. He sounds less like the stereotype. "People walk around here for entertainment. For me, it remains a place of evil. What angers me most is that society allowed the circumstances in which these disgraceful things could happen. This was compounded by the original crimes being poorly investigated by police. We have to wonder whether society would have let that happen if the victims had been school principals, politicians, football players."

Thirty years after Peter Sheil's death, his four siblings have no answers. In April 1983, Sheil's body was found with "multiple injuries" - but without trousers - at the base of a small cliff at Gordons Bay, then commonly known as Thompsons Bay, north of Coogee. Sheil, 29, was not gay. He was schizophrenic and was on medication, but on the night of his death he was in good spirits, says brother Hugh. Peter had called his mother from the Coogee Bay Hotel at about 8.30pm to say he was heading home to a halfway house in Clovelly. He chose the coastal walk. It passed known gay beats.

Sheil's mother was a devout Catholic. She could not countenance the possibility of suicide and the policeman who handled the case was helpful, perhaps too helpful. Christopher Sheil, then 27, witnessed the "inquiry" into his brother's death - a discussion between his father and the policeman. "It took all of about a minute. They got to the part on the form where you fill out cause of death. I can't remember whether it was Dad or the cop who suggested misadventure. I said, 'We don't know whether he jumped, fell or was pushed.' Dad said, 'Ah, we're not gunna go into any of that.' "

Their parents are now dead. Christopher, 58, says, "Peter definitely wasn't gay. I wouldn't be embarrassed at all if he was. It's just not accurate. However, his behaviour could be reckless and it is quite possible he was mistaken for being gay, and attacked for that reason. It might also have been suicide, although if you look at the point where he died, it's not a likely choice. It's only a couple of storeys high. There were plenty of higher cliffs along the way."

Hugh Sheil remembers Coogee's beats - and their poofter bashers. He can't remember any by name but he does recall how blithely they would announce they were going to "give the poofs a flogging".

In those times, somehow it didn't sound so shocking.

In 1990, Steve McCann and Sue Thompson were curious enough to wonder about Ross Warren. Bondi's Sergeant Ken Bowditch, who was in charge of that case, had been less curious. After investigating for four days, Bowditch concluded - no inquest required - that Warren had fallen accidentally into the ocean, and that his body would soon surface. It never did. McCann and Thompson wondered, too, about John Russell.

Russell, a former barman, had been due to leave Sydney for the Hunter Valley, where he intended to spend some of a $100,000 inheritance building a home on his father's property. The police report into his death found that another gay man at a gay beat had fallen accidentally - "no suspicious circumstances". In fact, there were plenty, not least the clump of blond hair clenched in his left hand.

Confronted with the Kritchikorn killing, McCann and Thompson decided to treat Warren and Russell as probable murders. It would be another 10 years before Steve Page launched Operation Taradale, a three-year investigation that would focus on Warren and Russell but also cover other deaths. Page's Taradale report would be tendered as the critical document in a 2003 inquest into the death of Russell and the suspected deaths of both Warren and Gilles Mattaini, a 34-year-old Frenchman who vanished from Bondi in September 1985, in what was possibly the first murder at Marks Park.

One thread explored in Taradale potentially linked David McAuliffe, of the Tamarama Three, to the Bondi Boys. On December 18, 1989, three youths approached a man near the Bondi Icebergs club in Notts Avenue, the road that adjoins the coastal walk to Marks Park and beyond. "Are you gay?" they asked before they punched and kicked him and struck him with a skateboard. They broke six of his ribs. The victim identified two of them from police photographs - David McAuliffe and a Bondi local called Sean Cushman. Taradale contains extensive claims against Cushman, mentioned as "the leader" of the Bondi Boys.

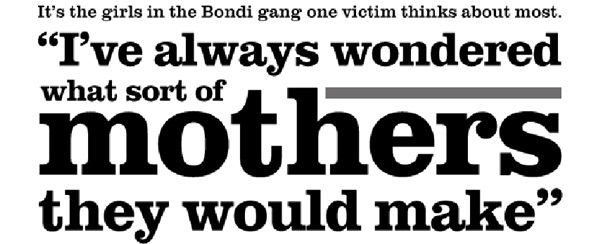

Three days after that attack near the Icebergs, another gay man, 24-year-old David McMahon, took a late-night jog along the coastal path. Returning to Bondi, he was metres from the steps to Notts Avenue when he was tackled. Four or five youths did the beating, but McMahon recalls there was gang of about 18 present, aged 15 to 20. Four of them were girls. "They were cheering them on, encouraging the boys," McMahon tells Good Weekend. Someone said, "Don't let him look at us. He knows me." Indeed McMahon, who worked at a cafe on Campbell Parade, had recognised them. They were already known for terrorising gays, he recalls. He says he will never forget the face of the gang leader or what he said: "Let's throw him off where we threw the other one off." They dragged him a few hundred metres, close to the spot where John Russell drew his last breaths less than a month earlier.

"I'm gonna throw you over the side," the leader had said. Somehow, McMahon seized a moment and escaped towards Bondi. He outran the gang. He scaled steps into Hunter Park and screamed to a middle-aged man on a balcony. "I don't help poofters," came the reply.

After hesitating, McMahon chose Cushman from police photographs. A local with a record of stealing and petty crime, Cushman denied it was him and there was no corroborating evidence.

McCann's secret tapes of the Alexandria Eight, meanwhile, were explosive in their apparently incriminating details. The 17-year-old storyteller mentioned a weapon in the unsolved murder of William Allen in Alexandria Park - a "screwie", or screwdriver - which seemed to match a hand wound. The youth and fellow gang member Ronald Morgan implicated three local associates. Dean Howard, their co-accused in the Richard Johnson case, named the same three, but he also suggested Morgan and another member of the Alexandria Eight. Police could place little credence in Howard's recollections - Morgan may have been out of Sydney at the time, the other gang member in New Zealand.

****************************************

McCann left the force. His files collected dust until the day in September 2000 when Steve Page opened a letter from Kay Warren, mother of Ross, the Wollongong TV newsreader. Her humble request for answers spawned Taradale. Page called in Sue Thompson. He re-interrogated the Alexandria Eight and the Bondi Boys - and girls - about the suspected murders of Warren and Russell and the attempted murder of David McMahon. He bugged the phones of the Bondi crew who, a decade older, seemed untouched by the enlightened new millennium's politically correct language.

They still spoke of "poofters" and the cops hassling about a "faggot" who "went off" Marks Park. Cushman and a mate speculated about which "psychos" might be killers, but nothing that would stick. Depending who among them Page's team spoke to, the Bondi Boys had also used the graffiti tags PSK - Park Side Killers - and PTK, for Prime Time Kings or Part Time Killers.

In one intercepted call, Cushman's mother told him two detectives had visited. A dead man "had a clump of blond hair and you're a suspect". She wanted his assurance that he hadn't been "giving fags a hard time". Cushman: "Nuh ... they can have my DNA ... I wouldn't lie to you, Mum."

In 2003, Page delivered Taradale, all 2638 pages of it, to the then deputy state coroner, Jacqueline Milledge. A tendered police document included a recollection by the Tamarama Three's Matthew Davis about what David McAuliffe had told him soon after they killed Kritchikorn - words to the effect: "Don't worry, brother. This isn't the first time we've done this. You're one of us now." It was only Davis's word.

Sean Cushman told the court: "We grew up in Bondi. That's why we called ourselves the Bondi Boys." But he said: "I was never in a gang or crew. We didn't roll homosexuals." He has never been charged with a gay-hate crime and did not respond to Good Weekend's requests for an interview, though his mother said he wouldn't be interested. Cushman was given a good behaviour bond in 1999 for being an accessory after the fact of a violent assault three years earlier, when he had helped a friend who had viciously attacked a British tourist. The tourist, Brian Hagland, fell into the path of a bus during the fight and later died of his injuries at St Vincent's Hospital.

Cushman, according to the Taradale report, also went to a house to collect a drug debt in 1999 and warned his target's mother that he had killed a man at Bondi and got away with it - and he would do so again because the "coppers are too fuckin' stupid".

Sue Thompson retired, injured, in early 2003. Page would leave the force the following year. But both returned to court in 2005 to hear Milledge's findings. She called it a "first-class investigation".

Milledge concluded, like Page, that Warren and Russell had been murdered. She described the original police investigation into Warren's death as "grossly inadequate and shameful" and Russell's as "lacklustre". John Russell had sustained multiple injuries "when he was thrown from the cliff on to rocks", but police had lost the one exhibit that might one day help identify his killer: the hair he had been clutching in his hand. "Disgraceful," said Milledge. She found that Gilles Mattaini had probably met a similar fate. But Milledge said there was insufficient evidence to recommend that anyone be prosecuted.

Peter Russell, John Russell's brother, recalls a stare-off with one of the eight "persons of interest" at the inquest. "I looked at him and he looked at me, and I just know he was John's killer. I don't have proof, but I know."

In Boston, Steve Johnson read the news. Until now, he had no idea that gay bashing had been such a blood sport in Sydney. He got to work.

Jean Dye didn't know it, but the police files listed her son Crispin's murder as a possible gay-hate crime. She is not convinced that was the motive. She does, however, want some answers, some 20 years after he was bashed to death in Little Oxford Street, off Taylor Square.

Crispin had been a long-time manager for rockers AC/DC who'd also worked with Rose Tattoo and the Easybeats as well as being a singersongwriter. On the night of December 22, 1993, he and friends celebrated the success of his first CD, A Heart Like Mine. About 4.30 the next morning, a witness saw three men of Pacific Islander appearance standing over Dye, 41, apparently going through his wallet. He died two days later, on Christmas Day.

He had many girlfriends, his mother says, though he had told her: "People say I'm gay, Mum, but I don't know what I am." Jean Dye cannot exclude the possibility that his attackers thought he was gay, or that they simply wanted his money. After a 1994 inquest, a policeman had told her that a prisoner had been captured in a secret recording saying that he had "knocked off" Dye. It came to nothing. She is unhappy to learn that a police reward for information has long since lapsed. "Somebody out there knows what happened," she says.

The case of 64-year-old Cyril Olsen seems much less ambiguous. Olsen, a homosexual, was bashed in a Rushcutters Bay gay beat on the night of August 22, 1992. Some time later, Olsen tumbled from a wharf in the bay and drowned. Police immediately identified it as a possible gay-hate crime. An anonymous caller would later name a man who had been heard saying on the same date: "Let's roll a poof tonight."

In jail for another offence, that man allegedly told a cellmate he had bashed a gay man who then died. He denied this when police questioned him. The coroner ruled Olsen "drowned after accidentally falling". Olsen's friend Brian Stewart attended the inquest and believes there was little alternative on the available evidence.

Olsen had been drinking heavily that night. "A taxi driver saw him, bare-chested and bleeding, and asked if he needed any help. He said, 'I'm perfectly all right, thank you.' "

But Steve Page argues that it makes no sense to exclude the brutal assault as being the cause of Olsen's fall. He runs his usual moral gauge over this case: "We wouldn't stand for it if it was a woman or child who had been bashed and then fell in the harbour."

The winter sun is making emeralds of the Pacific below Blue Fish Point. This is Rebecca Johnson's third visit to the cliffs where her brother died. "It's hard to be here," she says, "but at the same time, it's so beautiful." She can imagine him happy here. "I was 11 when he died. The narrative I grew up with was that Scott had killed himself."

Now she is 36 and she and Daniel Glick have made another trip to Sydney to check on the progress of the police investigation. "Of course, there is no solace in the more likely truth that he was thrown, naked, from a cliff. But I am glad he wasn't so unhappy that he wanted to take his own life. The murder, it's horrific, but there is comfort in knowing that."

David McMahon knows just how horrific. He is the gay man who got away. Working at his cafe soon after the attack, McMahon would see his attackers passing by. Ever since, he has sought to protect his identity. "I went into hiding, really. I was so shy and meek back then, I was the perfect target." But now McMahon is braver, and he wants to reclaim his name and put it to this story; not his photograph but his name.

"I am at the stage in my life when I can see that this terrible history of gay hatred is part of what we are as a society. We have moved on a lot, thankfully, and I have been part of that."

He hopes someone from the Bondi gang can find as much courage and finally come forward with the truth. It is the girls he thinks about most. "I've always wondered what sort of mothers they would make."

Some are, indeed, mothers - the Facebook page of one of them features a Holy Communion photograph. The Operation Taradale interviews in 2002 give some insight into the girls' thinking. "They all beat up their girlfriends," one said of the boys. Another, asked about their attitude to gays, said, "We probably didn't like them ... 'cause all the boys, you've got to impress them when you're young."

Some of the killers are fathers. It is hard to find any who will talk at all, let alone explain what possessed them then or what they think of their crimes now. One of the Alexandria Eight, however, does take the call at his workplace in the eastern suburbs. He has previously told police he was uneducated and easily led when he committed the crime. Today he is brief, but very polite.

"Obviously this is something that I think about all the time. It's something I deeply regret doing. I have kids of my own now, so I know how hard it would be to lose someone. But because I have kids, I have tried to put those days behind me."

His eldest is 16, the same age he was when he and his mates killed Richard Johnson. At some point, he says, he will have to sit his kids down and explain what he did.

*********************************************************

Suburbs where gay men were beaten or thrown to their deaths in a silent epidemic of homophobic violence over 20 years.

The horror they must have felt in their final moments would have been close to unimaginable, but for the dozens of men attacked and killed late at night at beachside cliff-tops and secluded parks across Sydney from the 1970s to the early 1990s, justice may be edging nearer for the loved ones they left behind as police and the local community slowly front up to the reality of an epidemic of gay-hate killings.

As NSW Police this week confirmed for the first time it was widening a review into the mysterious disappearances and deaths of a number of gay men across the state, the family of American maths genius Scott Johnson – now widely believed to have been the victim of a fatal gay-hate attack near Manly Beach in December 1988 – told the Star Observer many of the suspected crimes would have been solved if homophobic attitudes had not been so prevalent in the police force in decades past.

“It is a sad likelihood that police then knew or guessed what was going on but turned a blind eye because of their own prejudice, or because these victims had no voice,” Johnson’s sister Rebecca Johnson Arledge said. “Imagine if the victims had been almost any other group – 80 or 90 women, or children, or even blue-collar workers who were attacked and killed every few weeks. The public outcry would have been deafening; the police would not have rested.”

Last week the Sydney Morning Herald revealed that roughly 80 such deaths or disappearances from the late 1970s to the early 1990s that were originally ruled suicide or misadventure, mainly in Sydney, are now believed to have been murders. Sue Thompson, a lawyer and former state ombudsman’s investigator who joined NSW Police in January 1990 to co-ordinate its liaison with the LGBTI community, estimated 30 of those cases remain unsolved. Although some cases resulted in young men arrested and charged soon after the attacks, police officers at the time failed to link the string of assaults as a pattern of violence against gay men and men perceived to be gay.

Many of the attacks that took place at cliff-tops across Sydney’s eastern and northern suburbs, as well as several inner-city parks well-known as gay beats, are now believed to have been perpetrated by roving gangs of young men. With names both banal and brazen, groups like the Alexandra Eight, the Bondi Boys, the Tamarama Three and the Park Side Killers continue to cast a dark shadow over the city’s recent past.

“We believe that those responsible for these horrible crimes are still living free in our communities. Scott died only 25 years ago – if these were teenage gangs, the perpetrators are now in their forties,” Scott’s brother Steve Johnson told the Star Observer.

“For those who have heard about the gay bashings or witnessed them, it’s safer now to come forward. Times have changed in the police department. The police are keen to hear what you have to say.” Johnson was only 27 and about to be awarded his PhD in mathematics from the Australian National University in Canberra when his body was found at the bottom of Blue Fish Point lookout near Manly’s North Head.

Originally ruled as suicide both by local police and the coroner, the Johnson family’s tenacious fight to get to the truth of what happened to Scott saw them turn to celebrated Newsweek journalist Daniel Glick almost a decade ago after being spurred on by the findings of NSW coroner Jacqueline Milledge in 2005 in relation to a number of similar deaths.

Glick’s early investigations revealed that Blue Fish Point lookout was a well-known gay beat while at least six men, including WIN television newsreader Ross Warren, were believed to have died in similar circumstances at gay beats near cliffs overlooking Bondi in Sydney’s east between 1987 and 1990.

In June 2012 the NSW Coroner agreed to hold a new inquest into Johnson’s death, overturning the finding of suicide and bringing an open verdict with the matter now with the NSW Police Cold Case Unit. Earlier this year, a $100,000 reward was offered for information that may help solve Johnson’s death.

Tony Crandell, who was recently installed as NSW Police force’s corporate spokesperson for LGBTI people, told the Star Observer police were determined to solve what happened to Johnson as well as several other mysterious deaths.

“The cause of Mr Johnson’s death is still not determined, but detectives are committed to thoroughly re-examining all aspects of the case, including whether Mr Johnson might have been targeted because he was gay.

“Meanwhile, a review of Strike Force Taradale – an investigation into the deaths of two gay men and the disappearance of two others in Sydney’s Eastern Suburbs from 1985 to 1990 – was commenced by the Unsolved Homicide Team last year and is ongoing,” Crandell said.

“For investigative reasons, police had previously not announced that this review was taking place, but can now confirm that review is well advanced.”

The Star Observer understands the Homicide Squad will also be considering a number of other deaths with possible links to gay hate crimes in the 1980s and 90s for possible review.

Reflecting on the likelihood that Scott was one victim of many, the Johnson family told the Star Observer it was painful to think that so many other families were left with so many unanswered questions for so long.

“Victims’ families didn’t realise it was happening, so most didn’t object or believed they were alone with no recourse. They grieved their loss, as we did, with no answers or community,” Rebecca and Steve said.

“Times have certainly changed. Communities are openly talking about this dark era.”

INFO: Anyone who can assist police can call Crime Stoppers on 1800 333 000. Gay and Lesbian Liaison Officers (GLLOs) are also located at metropolitan and regional police stations across the state and anyone can speak directly to these specially-trained officers who deal with LGBTI issues.

This article is a follow-up article on the previous report from the Sydney Star Observer:

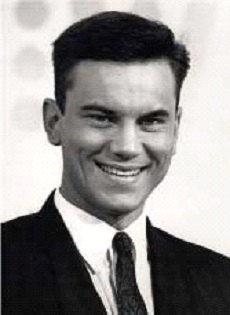

You may not know it looking at him today, but it is no understatement to suggest Alan Rosendale (pictured) is very fortunate to be with us. Now aged 56 and living in Newtown, Rosendale was viciously attacked by a gang of club-wielding “skinhead” thugs on a cold autumn’s night in May 1989 while walking through Moore Park on his way to his Surry Hills home after a night out with friends.

“They said something like: ‘There’s one – get him!’. I just ran. I think I actually fell, they didn’t push me into the gutter, and then they attacked me,” Rosendale told the Star Observer this week.

“I got a broken nose, I needed teeth work done and I was in hospital until the following Friday. I wasn’t in a good way and I was off work for about three weeks.”

Rosendale was only saved when a local gay man – Paul Simes – who happened to be driving on South Dowling Street flashed his headlights at the assailants and slowly drove past before taking down the registration of a car he had seen them leap out of. Simes quickly called the police from a nearby payphone on Cleveland Street and upon returning to the scene found the attackers had disappeared and Rosendale, who had been taken to St Vincent’s Hospital, was nowhere to be seen. Up until this month, Simes believed Rosendale may have been killed – another victim of Sydney’s gay hate epidemic that had been silently culling members of the city’s burgeoning gay community.

For a quarter of a century, Rosendale lived with the belief he was lucky to escape with a savage beating after being randomly picked on by a group of youths who had gone “poofter bashing” – an activity which a series of recent articles in the Star Observer, as well as the Sydney Morning Herald, have suggested was rife across Sydney from the 1970s to the 90s and led to the deaths of about 80 gay men in the space of a few decades.

“It was at a gay beat and it was at about one o’clock at night,” Rosendale recalls matter-of-factly. “I had just left the Taxi Club and I was probably half-pissed to be honest. I lived in Surry Hills – and it was on the way home – so I just popped in to see what was going on, and that [gay bashing] was what was going on.”

Then a 32-year old hospitality worker employed as a front-of-desk staffer at the Waldorf Apartments on Liverpool Street, Rosendale told the Star Observer he has been in a state of shock for the past week after happening across Simes’s account of the attack in an article published in the Sydney Morning Herald earlier this month.

“I’ve walked around for 24 years thinking that I was bashed by thugs, and then you find out one Saturday morning you weren’t bashed by thugs but by cops,” he says. “It’s amazing.”

The licence plate number Simes had noted down and given police matched the registration of an unmarked police vehicle. Simes was called in for a meeting with senior police weeks after the incident and told his report would be properly investigated, but was informed soon after that the officers from the ‘unassigned response unit’ allegedly responsible for the attack had been disbanded.

“The information that came out is that I was never interviewed and the only time I had contact with police was when I was being admitted to St Vincent’s Hospital,” Rosendale tells the Star Observer. “It was uniformed police and according to the incident report they put down that I had been bashed by a gang of skinheads. End of conversation.

“I gave my statement for what happened in 1989 on Tuesday of last week because no police ever interviewed me before then.”

Sydney MP Alex Greenwich told the Star Observer he has called on the Police Minister and State Ombudsman for a “proper investigation” into Rosendale’s case and that of other historical violent crimes against gay men across the city’s parks and beachside clifftops.

“While it will be difficult to do this so far after the events occurred, the community rightly expects that NSW Police act within the law and protect vulnerable people,” Greenwich said.

“Ongoing and widespread cultural change is required to ensure that no one thinks it’s okay to assault or abuse others on the basis of their gender or sexuality. I am working with the families of some of the victims towards justice.”

At the opening of the new Surry Hills police cell complex last Friday, Police Commissioner Andrew Scipione told the Star Observer that police were taking seriously revelations of links between gay-hate gangs and serving officers in decades past.

“We have full-time officers who work in those [LGBTI] communities and we have commanders from this area here today that police this area, and I know they would welcome anyone coming forward to give us information that might assist us in an inquiry that you might be wanting us to consider,” Scipione said.

Reflecting on his near-death experience at the hands of police, Rosendale says what worries him the most is that the officers involved in the assault upon him may still be in the force, and their superiors who failed to investigate may still be even higher in police ranks.

“Thinking about it now, I honestly believe I wasn’t the only one. They targeted me but I think they would have targeted others.

“After all this time to think that I was bashed by people who are there to protect me, it makes me feel disgusted,” Rosendale said.

“I thought things had changed since 1989. I thought things had changed a lot for the better but maybe they haven’t. I was very shocked when that guy was bashed at this year’s Mardi Gras.

“I really thought that when I was in the gutter and they were hitting me with their batons that I was going to die.”

In May 2008 the Australian Lesbian and Gay Archives received information, following a research inquiry, from Ian Purcell in Adelaide about the Memorial to Dr George Duncan which had been erected a few years ago. The photo of the plaque, erected along the River Torrens, near the site of the murder, was taken by Ian Purcell, and is shown here with his permission:

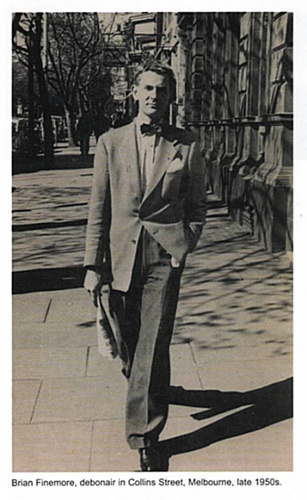

Brian Finemore, curator of National Gallery of Victoria, murdered in his home on 23 October 1975 - see article on Brian Finemore by Ian MacNeill in the September 2005 issue No.183 of Art Monthly Australia

Since entering the above item on Brian Finemore, the Editor of ART MONTHLY AUSTRALIA, Deborah Clark, and the author of the article on Brian Finemore in ART MONTHLY AUSTRALIA September 2005 No.183, Ian MacNeill have both given permission for the article to be reproduced in full here on our web pages. So here is the article:

It is difficult to do justice to Brian Finemore, especially if you have not experienced him. His friends and those who knew him are reduced to quoting epigrams such as ‘Camberwell is not so much a suburb as a state of mind’, which these days sounds thinnish because Camberwell, Melbourne and Australia have changed so much since the post-war needlessly austere world in which Finemore flourished and against which he kicked with all his might.

The wanton dullness, the mindless conservatism, the fearful resistance to change, the wilful blindness to opportunities for better things, the resistance to pleasure and to happiness that characterizes so much of Australian history – that terrible repressive grip has loosened considerably since Finemore’s death in 1975. Brian Finemore was born and bred in a world in which the word ‘cancer’ was not spoken, the cerebral palsied were locked up, many were locked up, homosexuals were locked up. Oh homosexuals were locked up in so many ways. And as a homosexual man of conscience Finemore must have felt obliged to rattle the bars.

A group of women who liked to ‘luncheon’, as I suppose they would have said, tittered at Finemore one day as he entered a society restaurant at the top of bourke Street with some friends. There they sat, in their vainglory, with hairdos you could have clad boilers in. Inevitably there was a lull in the lunchtime clatter, ‘Look at the hair,’ Finemore proclaimed in the restaurant, ‘you wouldn’t run your feet through it.’ People who were there dined out on it forweeks. But like all such stories about Finemore, it falls a little muffled. These days those who were not there smile politely, a little indulgently, at the anecdotes.

These days we are unfeeling and uncaring because we think interest rates will go up. The excuse Australia had ‘in those days’ (say, the fifties till the mid-seventies) was that it was led by people who had been traumatized by two world wars and an intervening Great Depression. Australians were grateful to have a job even though there was a labour shortage, terrified of what their neighbours thought, scared to think about what they themselves really thought and felt, suffered in silence and imposed silence on others. They were scared of life. Many sought escape from the institutionalized and self-imposed restrictions, the overwhelming dullness, by fleeing ‘overseas’.

Brian Finemore stayed. And defied. His clothes were noted as different – people who knew him described them as ‘tailored’, or ‘he designed them himself’. In his memoir The Bright Shapes and the True Names (Text, 2003) Patrick McCaughey says of Finemore that ‘he always appeared to belong to another Melbourne than the present one’.* So we get a sense of Finemore as a tailored dandy, perhaps at pains to promote an idea of himself as from the Establishment. He was tall and elegantly slim, he had words for every occasion. He was a regular guest at Government House, no doubt to help Sir Dallas and Lady Brooks cope with some of the more tedious guests. Mind you, he did not mince his words – that was part of his charm, the thrill of dining with a panther. Of the President of the Board of Trustees of the National Gallery of Victoria, Finemore said you could always tell which was the glass eye – the one with the feeling in it. ‘Dear Madam, No.’ was how he once responded to a letter to the National Gallery of Victoria (NGV).

Brian Finemore was the first curator of Australian art to be appointed in this country. By the mid-twentieth century Australia had produced its own plein air school, Margaret Preston, the Antipodeans, Albert Namatjira – a national art. It says much for the Melbourne establishment of those days that it could at least conceive of such a position even if they had no intention of making the incumbent’s life easy. The rest of Australia certainly lagged behind. Finemore got the job at the NGV in 1959, on the recommendation, it seems, of Joseph Burke, Professor of Fine Arts at the University of Melbourne (‘the shop’) where Finemore made uneven and interrupted progress to take his degree in 1963, after a break of ten years between 1948 and 1958. The groves of academe seem to have been in some ways uncongenial to him but were necessary if he was to pursue a career in his chosen field, Fine Arts.

Finemore was a member of the Twenty Club, formed out of a desperation to get a decent conversation in Melbourne. Its founding members included Bernard Smith, Vance Palmer, Frank Davison, Alan Marshall, Ian Turner and Judah Waten – no women and no right-wingers, it would seem. Eric Westbrook, the Director of the NGV during most of Finemore’s employment there, was also a founding member.

Finemore’s championing of the nineteenth-century larrikin artist S T Gill suggests that if he was not strictly left wing himself he had a deep sympathy for the life of the workers. He admired Gill’s ‘robust humour’, his ‘acute observation of typical occupations and characters’ and the fact that Gill ‘introduced a wide variety of scenes from popular art into Australian art’. Gill’s Views of Melbourne celebrated the charms and splendours of the city that Finemore loved for all of his fifty years. He also noted that Gill ‘fell dead in the street in Melbouren, penurious and forgotten.’ Finemore himself was a great favourite of the NGV attendants and he always made sure his unpretentious parents were comfortable at the Gallery’s functions.

Finemore’s achievements were not chiefly academic, though his essay on the ‘Australian Impressionists’ is admired and has proved invaluable. It can be found in the tellingly titled Freedom from Prejudice, a book of Finemore’s writing on the collection of Australian art in the National Gallery of Victoria, assembled by colleagues and friends after his death. His pamphlet Painting, published in the early sixties as part of Longman’s The Arts in Australia series has had an inestimable influence as an introduction to Australian art and been much used as a school text. Finemore worked quietly to give Eugene von Guerard his present eminence and encouraged the NGV to acquire works by Grace Cossington Smith, Roy de Maistre and Roland Wakelin when the reputation of these modernists was at a low ebb. He paid for trips to Sydney himself in order to scout and to secure these works and to prevent himself from turning into a ‘curator of Melbourne art’. There were also occasions when Finemore paid exhibiting artist himself rather than lose their commitment. At the time all the NGV staff from the Director down were very poorly paid.

Finemore is best remembered for his shows. He organisd twenty exhibitions during his sixteen-year career at the NGV. At least four were outstanding: Australian landscape painting (1964), The field (1968), Heroic landscape (1970) and Object & idea (1973). The field and Object & idea in particular seem to have been attempts by Finemore to persuade Australia to embrace the new, to shrug off the dreadful limiting past.

The field opened the NGV at its new premises on St Kilda Road in 1968, and featured paintings in the new international abstract style known variously as ‘minimal’, ‘hard edge’, ‘flat field’ and ‘colour field’. The works of sculpture/installations exhibited in it were spare, tending to the geometric and ranged from the delicate and witty to the industrial monumental. Many were colourful. Of course the opening of the new premises was a hugely important event for the art world, and those excluded by Finemore’s curatorial choices were peeved and, in the nature of the selection process, many. The Antipodean group seem to have been particularly angry that their eminence had not been so recognized. Albert Tucker was at pains to make his disapproval of The field known as widely as possible.

Critics of The field claimed that it was merely fashionable, that the show lacked depth and range and, worst of all, significant works of art. Time has to some extent validated that claim. However, The field is still mentioned in works of Australian art history as having great significance, bringing a new internationalism and, most importantly of all, an excitement to the Australian art scene. The beautiful catalogue produced for the show gives an idea of the glamour and brilliance of its effect – dazzling colours vibrate in striking geometric patterns and blur in fascinating optical illusions. The sculpture fibrillates and ponders. Exhibitions Officer John Stringer, who worked closely with Finemore on all aspects of this exhibition, set much of this off against a silver tin foil background. It is easy to see why the somberly repressed Tucker was outraged.

Finemore courted controversy. But he also worked to free Australian culture from a convention-bound parochialism and a nationalism that had begun to be stifling. He had the verve and strength to follow the controversies of The field with the Object & idea exhibition, which offered a further challenge of what art is and may be. In an essay written in 1962 (republished in Freedom from Prejudice), Finemore argued for an Australian scholarship to support the works of art held in the nation’s collections. People often came away perplexed from exhibitions because there was no accompanying catalogue to offer them a guide. And there were no catalogues because there was no-one to write them.

Finemore argued that a true Australian art scholarship would create a common ground between artists and spectators, and between artists and the foremost scientific, literary and social and political thinking. He himself made a significant contribution towards these ends. Australians now flock enthusiastically to exhibitions of Australian and contemporary art; they hang art on their walls and have it standing in their living rooms and gardens and, they read about it and understand something of its history.

Brian Finemore’s murder on 23 October 1975 shocked and scandalized Melbourne. The crime remains unsolved.

GAY AND LESBIAN HATE CRIMES - BIBLIOGRAPHY AND RECOMMENDED READING LIST