To read any of the obituaries of the people listed, click on their name and you will be taken to the particular item.

|

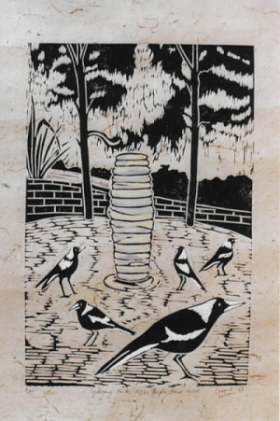

This linocut was done by Lenore Bassan for the SPAIDS Reflection Area in 2006 |

When the microphones were off and the crowds had gone home, Larry Kramer was a different person: sweet, thoughtful, and generous.

For many years, I regarded Larry Kramer as the most annoying and abrasive man in America. There was no No. 2. No one even came close. I will never forget our first encounter, in 1986, when he called me a “Nazi” and a “murderer” while he was testifying before hundreds of people at a public hearing at the headquarters of the Food and Drug Administration.

I had just begun to cover the AIDS epidemic for the Washington Post, and Kramer was speaking before an advisory panel that was considering whether to approve a new treatment for one of the more debilitating AIDS-related infections. Kramer felt that the government, the media, and the public-health establishment had mostly ignored AIDS because, in America at the time, it was regarded solely as a “gay” plague. He was being hyperbolic—his tantrums often were. But he was also sick of the horrors he had witnessed: the tepid and bigoted federal response to a disease that would kill hundreds of thousands of Americans. Although the epidemic had first appeared in 1981, President Ronald Reagan did not publicly utter the word “AIDS” until 1985—at a press conference. Government scientists were treating the virus as yet another interesting phenomenon that required investigation and treatment, but were doing so without much urgency. Kramer had had enough. I was not the only “murderer” in the auditorium that day. He denounced many people, including his foremost enemy at the time, Anthony Fauci, who since 1984 has directed the federal response to AIDS. There were almost no horrible names that Kramer failed to call Fauci: he, too, was a murderer, and also incompetent, evil, and a homophobe.

So it might be surprising to read the e-mail that Fauci sent me on Wednesday morning, upon hearing of Kramer’s death at the age of eighty-four. “This is a very sad day for me and for so many others involved in the HIV/AIDS struggle over so many years who have had the opportunity to know and interact with Larry Kramer. A veritable icon has passed after a life of enormous impact.”

Fauci, whom I profiled last month for The New Yorker, loved Kramer, and so did I. The word “icon” is terribly overused, but even clichés have a purpose. It took me a while to see Kramer’s genius, because he was so outrageously belligerent and confrontational. His default mode of speech was the primal scream. To be honest, he scared me. It took me too long, but, eventually, I learned to look through the anger, resentment, and fear. When I did, I realized that Kramer was right—about almost everything. He could not understand why the F.D.A. was responding so slowly to a disease that was killing so many people he loved. He was convinced that if the virus had emerged first in heterosexuals—as it did in Africa, which has been devastated by the epidemic—there would be no such hesitation. By the time we met, Kramer was a fully armed instrument of rage.

His impact on American society was soon hard to ignore. By the end of the nineteen-eighties, Kramer had launched the two most effective AIDS advocacy organizations in the United States. In January of 1982, Gay Men’s Health Crisis was formed, at a meeting in his Greenwich Village living room. Several years later, infuriated by the inability of conventional activists to have an impact on AIDS drug approvals, Kramer started the AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power— better known as ACT UP. The group, which combined aggressive confrontation with brilliant research into the arcana of clinical drug trials, was the most effective political action group I have ever seen. Kramer told me that both organizations were conceived in ?ashes of pure rage. (A fact that he noted with pride.)

Video From The New Yorker Departing GestureKramer’s unflinching activism also set American medicine on a course that fundamentally altered the relationship between doctors and their patients. It became inconceivable for federal scientists to consider a drug or treatment protocol without including at least someone who actually had the disease they were investigating. Patients who had been trained to be docile and accepting came to doctors’ appointments with reams of data and genuine demands. This is how Fauci described the phenomenon in “Public Nuisance,” my Profile of Kramer for The New Yorker, in 2002. “In American medicine, there are two eras. Before Larry and after Larry. .?.?. There is no question in my mind that Larry helped change medicine in this country. And he helped change it for the better. When all the screaming and the histrionics are forgotten, that will remain.”

It is essential to think about what Kramer’s world looked like in 1983, when he wrote a six-thousand-word screed in the New York Native called “1,112 and Counting.” It referred to the number of people who had, at that point, died of AIDS. Today, the number is close to forty million. The piece became one of the most-read articles ever printed in a gay publication. “If this article doesn’t scare the shit out of you, we’re in real trouble,’’ Kramer, began. “If this article doesn’t rouse you to anger, fury, rage and action, gay men have no future on this earth. Our continued existence depends on just how angry you can get. .?.?. Unless we ?ght for our lives we shall die.’’

When we were alone, when the microphones were off and the crowds had gone home, Kramer was a different person: sweet, thoughtful, reflective, and generous. “I am extremely shy,’’ he once told me. “People, when they meet me, are always shocked that I’m not foaming at the mouth or shouting obscenities.” Every time I walked the streets of Greenwich Village with him, men approached Kramer and thanked him for saving their lives. He was humbled by those encounters and proud of them, too. Kramer lived in an apartment at 2 Fifth Avenue, as did his nemesis, the New York mayor Ed Koch, who Kramer believed did little to help gay men during his tenure leading the city. One day, years after Koch left of?ce, Kramer ran into the former mayor in the building’s lobby. “I was getting my mail,’’ Kramer told me, and, “suddenly I looked up and Ed Koch was standing right in front of me. He was trying to pet my dog Molly and he started to tell me how beautiful she was. I yanked her away so hard she yelped, and I said, ‘Molly, you can’t talk to him. That is the man who killed all of Daddy’s friends.’ ”

This is the third time I’ve written an obituary of Kramer. In 2001, with his liver ravaged by hepatitis B, Kramer underwent a transplant at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center. He was close to death, and, after a difficult thirteen-hour operation, one news service sent out what seemed like the inevitable headline: “AIDS ACTIVIST LARRY KRAMER DIES.’’ Kramer laughed when he saw it. “That is as good as Dewey beats Truman,’’ he told me at the time. Nearly a decade ago, he was hospitalized again, for weeks, amid a swarm of infections. He had become impossibly weak and frail. Friends of his told me to get an obit ready, because they were certain it would be needed soon.

So, finally, Kramer has left us. I am not sure what I will do without him. For the past thirty-five years, right up to our final conversation, three weeks ago, he has just been there—screaming, bickering, and, on occasion, even praising me. We also ended up laughing a lot. And once in a while, when AIDS had claimed yet another life we both had cherished, we cried together, too. Today, I am crying alone. You made an enormous difference in this world, Larry. I will miss you.

Michael Specter has been a staff writer at The New Yorker since 1998. He is an adjunct professor of bioengineering at Stanford University and the author of “Denialism.”

The following interviews illuminate what motivated Larry Kramer and his activism:

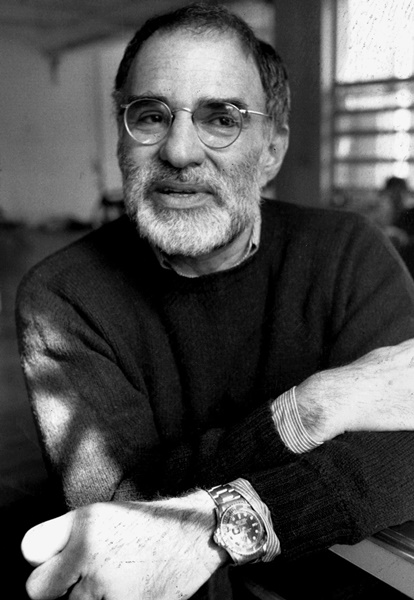

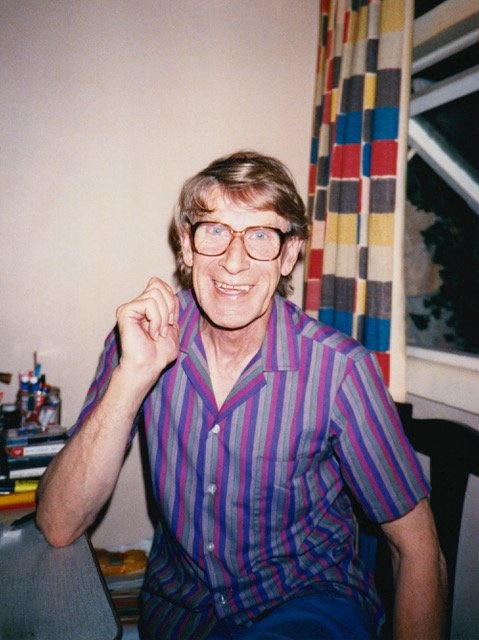

Portrait by Ken's friend Brenda Humble, painted in 1998 in Sydney

These two photos were taken by Gary Jaynes on 7 October 2020 the day after Ken's 98th birthday.

Ken died on 21 October, 15 days later.

We had 27 unforgettable years together in Sydney, Newcastle and - for the last 20 of those years - in Melbourne.

Sadly just a few short weeks after turning 98, 78er Kendall Lovett has passed away. Ken is survived by his partner of 27 years, Mannie De Saxe.

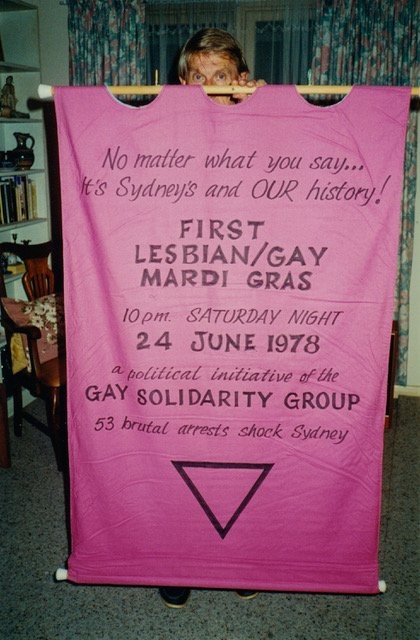

Ken was a tireless activist and campaigner for LGBTQI, refugee and human rights. Every demonstration that Gay Solidarity Group, later Lesbian and Gay Solidarity, organised from the late 70s onwards had Ken’s placards, banners, slogan vests or people-shaped placards – all in his distinctive calligraphy.

Ken was a lovely supportive colleague in the Gay Solidarity Group (GSG), which organised the first Mardi Gras and coordinated the massive Drop The Charges campaign that followed.

Ken joined GSG after the first Mardi Gras in 1978, and was arrested in the August demonstration in Taylor Square. Often during Mardi Gras parades and demonstrations, Kendall was waiting on alert with bail money ready. Ken stayed active in GSG, later renamed Lesbian and Gay Solidarity into the 2000s, after he and Mannie moved to Melbourne.

Ken had been active in Gay Liberation after he returned to Sydney from the UK in the late 1960s, and took part in the 1972 demonstration outside St Clement’s Anglican Church at Mosman after they had dismissed Peter Bonsall-Boone from staff. Kendall’s main political activism prior to GSG in 1978 was in a resident actiongroup saving Woolloomooloo from developers, with the support of the Builders’ Labourers Federation Green Bans in the early 1970s.

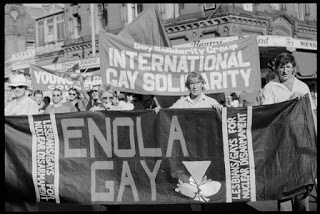

Ken was very active at the time of the nationalist bicentenary in 1988, helping organise a big queer contingent in the First Nations mobilisation, around the slogan “200 years of oppression and bad taste.” He was involved in Enola Gay, the peace and antinuclear activist group, and founded “Inside Out” a network supporting gay and lesbian prisoners. Ken was one of the people in GSG who was very involved with international solidarity. He sustained a long correspondence with anti-Apartheid gay activist Simon Nkoli when he was in prison in South Africa on treason charges.

In the early 1980s Ken and GSG were active in organising around inclusion of homosexuality in the NSW Anti-Discrimination Act, in demanding removal of the anti-buggery law and in responding to the rise of the Christian Right. Just prior to American Jerry Falwell’s visit in 1982, Kendall and Leigh Raymond registered the name, Moral Majority, and used it to campaign against Fred Nile and Falwell.

Ken also supported the Gaywaves radio program on 2SER FM over many years. He provided a weekly news bulletin – GRINS (Gay Radio Information News Service) – sometimes as a collective effort, but mainly as a one-man band, week in and week out. This was circulated to other lesbian and gay media across the country.

Ken was a key member of the Sydney collective of Gay Community News (1980-82) and the organising body for the Sixth National Conference of Lesbians and Homosexual Men in Sydney (1980). He was also a correspondent to gay newspapers overseas and the International Lesbian and Gay Association (ILGA).

In October 1982 Ken and GSG supported Roberta Perkins and the Australian Transsexual Association (ATA), in staging the first transgender protest in Australia, in Manly. The protest was held to challenge a judgement against two transwomen, who a Magistrate had ruled were men. In response the NSW Attorney-General said that ‘Attorneys-General of the six states had committed to new legislation to recognise the validity of sex changes’.

In 1985 the Sisters of Perpetual Indulgence canonised him, in recognition of his extensive gay activism, as St Kendall the Constant.

Kendall formed a relationship with Mannie De Saxe, a revolutionary socialist and Jewish anti-Zionist activist from South Africa, after they met in GSG. Both of them remained active in lesbian and gay, and other social justice, causes. They volunteered to help people with AIDS, and founded SPAIDS, which planted a memorial grove of trees in Sydney Park.

After retiring from his job at Choice magazine, Ken moved to Newcastle. Twenty years ago, Ken and Mannie moved to live together in Melbourne and in recent years had practical home support from otheractivists and friends.

Ken and Mannie have been very engaged in the Australian Lesbian and Gay Archives. They have made big contributions to the struggle to improve services for older lesbian, transgender and gay people. Ken and Mannie were featured in the “2 of Us” in Good Weekend magazine on March 10, 2007. But they were very angry in 2009 when the government, as part of a path to marriage equality, decided they were a couple and cut their pensions, even though they had been independent tax payers.

Ken and his long-term support for LGBTQI and othersocial change struggles will be sadly missed.

Our condolences to Mannie and to Ken’s many friends.

We are sad to report that a few weeks after turning 98, 78er Kendall Lovett has passed away. Ken is survived by his partner of 27 years, Mannie De Saxe.

Ken was a tireless activist and campaigner for LGBTIQ, refugee and human rights. Every demo from the late '70s onwards had Ken’s placards, banners, slogan vests or people-shaped placards – all in his distinctive calligraphy.

Ken joined GSG after the first Mardi Gras in 1978, and was arrested in the August demonstration in Taylor Square. Often during Mardi Gras parades and demonstrations, Kendall was waiting on alert with bail money ready. Ken stayed active in GSG, later renamed Lesbian and Gay Solidarity into the 2000s, after he and Mannie moved to Melbourne.

Ken had been active in Gay Liberation after he returned to Sydney from the UK in the late 1960s, where he was part of the move for homosexual law reform. He took part in the 1972 demonstration outside St Clement’s Anglican Church at Mosman after they had dismissed Peter Bonsall-Boone from staff. Kendall’s main political activism prior to GSG in 1978 was in a resident action group saving Woolloomooloo from developers, with the support of the Builders’ Labourers Federation Green Bans in the early 1970s.

Ken was very active at the time of the nationalist bicentenary in 1988, helping organise a big queer contingent in the First Nations mobilisation, around the slogan “200 years of oppression and bad taste.” He was involved in Enola Gay, the peace and antinuclear activist group, and founded “Inside Out” a network supporting gay and lesbian prisoners. Ken was one of the people in GSG who was very involved with international solidarity. He sustained a long correspondence with anti-Apartheid gay activist Simon Nkoli when he was in prison in South Africa on treason charges.

In the early 1980s Ken and GSG were active in organising around inclusion of homosexuality in the NSW Anti-Discrimination Act, in demanding removal of the anti-buggery law and in responding to the rise of the Christian Right. Just prior to American Jerry Falwell’s visit in 1982, Kendall and Leigh Raymond registered the name, Moral Majority, and used it to campaign against Fred Nile and Falwell.

Ken also supported the Gaywaves radio program on 2SER FM over many years. He provided a weekly news bulletin – GRINS (Gay Radio Information News Service) – sometimes as a collective effort, but mainly as a one-man band, week in and week out. This was circulated to other lesbian and gay media across the country.

Ken was a key member of the Sydney collective of Gay Community News (1980-82) and the organising body for the Sixth National Conference of Lesbians and Homosexual Men in Sydney (1980). He was also a correspondent to gay newspapers overseas and the International Lesbian and Gay Association (ILGA).

In October 1982 Ken and GSG supported Roberta Perkins and the Australian Transsexual Association (ATA), in staging the first transgender protest in Australia, in Manly. The protest was held to challenge a judgement against two transwomen, who a Magistrate had ruled were men. In response the NSW Attorney-General said that ‘Attorneys-General of the six states had committed to new legislation to recognise the validity of sex changes’.

In 1985 the Sisters of Perpetual Indulgence canonised him, in recognition of his extensive gay activism, as St Kendall the Constant.

Kendall formed a relationship with Mannie De Saxe, a revolutionary socialist and Jewish anti-Zionist activist from South Africa, after they met in GSG. Both of them remained active in lesbian and gay, and other social justice, causes. They volunteered to help people with AIDS, and founded SPAIDS, which planted a memorial grove of trees in Sydney Park.

After retiring from his job at Choice magazine, Ken moved to Newcastle. Twenty years ago, Ken and Mannie moved to live together in Melbourne and in recent years had practical home support from other activists and friends.

Ken and Mannie have been very engaged in the Australian Lesbian and Gay Archives. They have made big contributions to the struggle to improve services for older lesbian, transgender and gay people. Ken and Mannie were featured in the “2 of Us” in Good Weekend magazine on 10 March 2007. But they were very angry in 2009 when Social Security, as part of a path to marriage equality, decided they were a couple and cut their pensions, even though they had been independent tax payers.

Ken and his long-term support for LGBTIQ and other social change struggles will be sadly missed. Our condolences to Mannie and to Ken’s many friends.

- Tribute written by Diane Minnis and Ken Davis, the Co-Chairs of First Mardi Gras Inc., a community association for 78ers. 78ers.org.au.

The world is a better place today, thanks to Kendall Lovett. Ken exuded enormous energy and creativity as a community campaigner and movement linchpin who identified with all who are exploited.

Ken died peacefully at home in Melbourne, where he lived with his partner of 27 years, Mannie De Saxe. He was 98 and remained active until the end, responding to emails and sharing political news.

My earliest memories of Ken were in 1980. I’d travelled to Sydney to participate in the 6th National Homosexual Conference, which Ken helped organise. He was living in a small townhouse in the inner suburb of Woolloomooloo. His home also housed boxes of material, carefully organised for archiving — a lifelong tradition, which the Australian Lesbian and Gay Archives will long thank him for.

Ken was proud of his working class community. He’d been an activist with Residents of Woolloomooloo (ROW), which won the crucial support of the Builders Labourers Federation. A green ban, in place for two years, from 1973 til 1975, prevented the suburb from being bulldozed, gentrified and replaced with skyscrapers.

The ‘70s was an explosive period for Gay Liberation. Ken was in the thick of it from the get-go. After the arrests at the first Mardi Gras in 1978, Ken joined Gay Solidarity Group (GSG). He was arrested during the tumultuous campaign to drop the charges, which followed. The movement in this period was militant, liberationist and multi-issue. This was reflected in the refrain that rang out through the streets of Darlinghurst to “stop police attacks, on gays, workers, women and blacks.”

GSG drew the connections between LGBTIQ oppression and the struggles of all the oppressed — this solidarity was at the core of Ken’s activism. He was a voluminous letter writer. This included writing to gay prisoners, through the prisoner support group, Inside Out. Ken had a long correspondence with Tseko Simon Nkoli — the Black, gay, anti-apartheid activist who was diagnosed with HIV while in jail on treason charges. Nkoli became internationally known in the ‘90s when he went public about his sexuality and HIV status at a time when the stigma in South Africa was immense.

Ken’s commitment to challenging racism ran deep. He joined many marches to stop Aboriginal deaths in custody. In 1988, he rejected the gross nationalistic jingoism and joined up with Gays Against The Bicentenary. On January 26, “Invasion Day,” First Nations people from across the continent led the 40,000-strong March for Justice, Freedom, and Hope. Marching alongside Ken and the huge queer contingent with my FSP Comrades is one of my enduring memories.

In 1993, after Ken retired from his job with the consumer advocacy magazine, Choice, he moved to Newcastle. Then early this century, Ken relocated with Mannie to Melbourne. He had met Mannie, a socialist and anti-Zionist Jew, through GSG. In Melbourne the pair continued organising, carrying on the traditions of marching against war, in support of Palestine and for refugee rights. Ken made many unique banners, signs and a host of innovative protest artefacts. He was also a prodigious photographer. In the days before digital photography, when documenting rallies was more costly, he captured and carefully labelled many hundreds of photos.

As well as being regularly out on the streets, Ken was also a movement builder, contributing a great deal behind the scenes. This included community media. He was part of the Sydney Collective for Gay Community News. For 10 years, from 1983 to 1993, he produced the Gay Radio Information News Service (GRINS). He researched and wrote the scripts for this weekly gay news service — recording the bulletin each week and packaging and mailing cassette tapes around the country to be played on community radio stations, including 3CR in Melbourne and 2SER in Sydney.

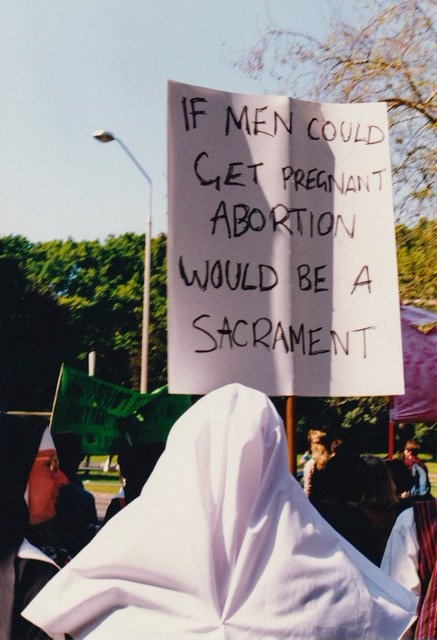

Ken’s passion for feminism was legendary. He supported reproductive justice, frequently challenging anti-choice bigots. He also went nose to nose against the right wing, embracing many creative tactics. He was part of a duo that registered the trade mark Moral Majority in Australia ahead of a visit by Jerry Falwell in the ‘80s. He then designed a selection of bright yellow Moral Majority ™ stickers declaring support for a pantheon of radical causes! He also had a long record of protesting the vile Fred Nile!

He was a mainstay of the Sydney Park AIDS Memorial Grove (SPAIDS), and after moving to Melbourne, he helped push Northern Melbourne Institute of TAFE into re-opening the AIDS Memorial Garden at Fairfield.

Ken supported the work of the Freedom Socialist Party since our Australian Section was founded. He was one of the first Australian subscribers to the Freedom Socialist newspaper and kept his subscription current for almost 40 years. He wrote a piece for the Freedom Socialist Bulletin about the need to resist discrimination sparked by HIV/AIDS, and we published many of his photos. Ken never missed donating to our regular fundraising drives. Ken was always pleased to get behind socialist projects — the month he died, he and Mannie had a large sign outside their house, advocating a vote for the socialist candidate in the local council election.

We celebrate the life of Ken Lovett as one very well lived. He will be missed by many, but especially Mannie. His legacy will long continue to provide inspiration for all who have a passion for justice.

From Red Flag

Ninety-eight years old and Ken Lovett hadn’t stopped! Ever the activist, while facing terminal cancer, Ken made sure he posted his voting papers for Victorian Socialists’ candidate Omar Hassan in the 2020 local council elections. He died just a few days later, politically committed to the end.

Ken lived through economic depression, world war, McCarthyism and then the hope of the late 1960s and early 1970s, when revolutionary struggles swept the world. This life experience made him a passionate campaigner in the fight against oppression.

In the mid-1960s, when living and working in London, he joined the Albany Trust, an educational, counselling and research organisation that worked alongside the Homosexual Law Reform Society. Law reform was partially won in the UK in 1967, but the Albany Trust continued its valuable work.

When Ken returned to Sydney, he threw himself into the still very new LGBTI+ activism, joining the lively Homosexual Law Reform group there. In 1972, when Peter Bonsall-Boone was dismissed by the Church of England after he came out on ABC TV’s Chequerboard program, Ken joined the rally outside the church. It was to be the first of many protests in Sydney, Newcastle and Melbourne.

When the Sydney suburb of Woolloomooloo, where Ken lived, came under threat from corrupt and greedy developers, he co-founded the activist group Residents of Woolloomooloo. Backed by the New South Wales Builders Labourers Federation, he was part of the world-famous battle to save this important working-class suburb. He was also a keen environmentalist and anti-nuclear activist, joining protests as part of the LGBTI+ Enola Gay group, named after the US plane that bombed Hiroshima on 6 August 1945.

As the LGBTI+ activist movement grew, he was involved in groups such as the Gay Solidarity Group, later Lesbian and Gay Solidarity, which organised the first Mardi Gras in 1978. Hundreds, including Ken, were arrested in Sydney during 1978 in the demonstrations for gay rights and Ken was heavily involved in the successful Drop the Charges campaign arising from these protests. The charges were eventually dropped, but the campaign also won the right to protest without a permit in New South Wales, a victory not just for LGBTI+ people, but for everyone.

From 1978, Ken was involved in countless groups, protests and campaigns, including the Sydney-based Gay Radio Information News Service in the Gaywaves program on Radio 2SER and the Gay Community News Sydney Collective. His stand against right-wing homophobes led him to join the Coalition Against Repression which organised protests during the visit of British homophobe Mary Whitehouse.

In the 1980s, he and others campaigned against another visiting homophobe, this time the US Christian preacher Jerry Falwell. As his friend Ian McIntyre recalls, they cheekily registered the name Moral Majority—a name previously associated with Falwell and other right-wing homophobic, sexist groups. Under that name, they put out badges, T-shirts, banners, stickers and press releases, all proclaiming that the Moral Majority supported gay rights, abortion, women’s and trans’ rights and so on. Ken himself was a strong supporter of women’s rights.

He was anti-racist and an internationalist to the core. He had a long-term correspondence with Black, anti-Apartheid, gay activist Tseko Simon Nkoli after he was jailed in South Africa on treason charges. Nkoli became known around the world in the 1990s, when he went public about his sexuality and HIV status at a time when the stigma in South Africa was immense.

Ken was also involved with Inside Out, an Australian gay prisoner support group, and marched to protest Aboriginal Deaths in Custody. He was part of the big Gays Against the Bicentenary contingent that joined the tens of thousands in Sydney on 26 January 1988 to protest Invasion Day. Then there was the Gay and Lesbian Immigration Task Force NSW and Friends of the ABC that he was involved in, and he was equally committed to Palestinian, refugee, anti-war and other human rights causes.

In October 1982, Ken and the Gay Solidarity Group supported Roberta Perkins and the Australian Transsexual Association in staging the first transgender protest in Australia. The protest was held to challenge a ruling that two transwomen were men. In response, the NSW attorney-general gave an assurance that all states had committed to recognising sex changes.

One of Ken’s abiding causes was for people with HIV-AIDS, volunteering for and supporting two HIV-AIDS garden memorials in Sydney Park and the Melbourne suburb of Fairfield.

More recently, and while not himself wishing to marry, Ken was a strong supporter of the marriage equality campaign, attending every Melbourne protest he could. He wrote thousands of letters of protest, submissions to enquiries and often designed and produced his own banners with his own distinctive writing style and imaginative slogans.

Twenty-seven years ago, he met his dearly loved partner Mannie de Saxe, a committed socialist, anti-Zionist Jewish activist, a South African and fierce opponent of that country’s apartheid regime. Together, they campaigned for so many of these and other causes, for equal rights for all, including, more recently, many contributions to improve services for older lesbian, transgender and gay people.

We have all lost a committed fighter for our rights, but one who has enriched the struggle and helped give us the strength to keep on fighting.

Liz Ross is a socialist activist and historian. She is the author of several books, most recently Stuff the Accord! Pay Up!, available from Red Flag Books.

Vale Kendall Lovett who passed away yesterday at 98. Condolences to Mannie and all others who knew and loved him. As a founding member of the Gay Solidarity Group/Lesbian Gay Solidarity, the Residents of Woolloomooloo Action Group, the Sydney Park AIDS (SPAIDS) Grove project, Gaywaves radio program, Gay Radio Information New Service (GRINS) and others Ken was in the thick of many political and cultural projects and struggles. His fine pen and signwriting skills saw him help create innumerable posters, flyers and banners, an example of which, with him in the middle, can be found below. We became friends about 12 years ago and my family appreciated the beautiful cards he wrote us on behalf of himself and Mannie, often adorned with photos from the pair’s past.

Ken was one of the loveliest people I’ve had the fortune to know, a true gentle man. When I first met him, he and Mannie were involved in lobbying NMIT to maintain the Fairfield AIDS Memorial Garden that the TAFE had inherited when they took over the former Fairfield hospital site. Although only occasionally attending rallies by that time he kept up letter writing and lobbying work around gay and lesbian rights, seniors issues, environmental causes and more, pretty much up until the end.

I enjoyed hearing his memories of growing up and of gay life from the 1940s onwards. Gay Solidarity Group/Lesbian Gay Solidarity lived up to their name and for decades Ken attended rallies for just about progressive issue imaginable, always with a banner and always out and proud. He had many stories of cheeky and funny actions, including attending a counter-demo against anti-abortionists in 1978 where he carried cardboard cut outs of friends who couldn’t be there. They were subsequently trashed when he and many others were arrested. In the 1980s he was one of a group of radicals who registered themselves as the Moral Majority ahead of a visit from corrupt US evangelist Jerry Falwell. They put out various pro-GLBTIQ, pro-choice and other statements, stickers and t-shirts under the official name. He lived an incredibly full life, some of which is documented on his and Mannie’s website - http://www.josken.net/

I’m really going to miss him.

Aidy Griffin, strategic driver of law reform and social inclusion of sex and gender diverse people, passed away in a hospice on Thursday 7 October 2021, at the age of 67. Aidy worked with others and then local state MP Clover Moore in the mid nineties to draft the first transgender recognition and anti-discrimination bill in the western world. That bill lapsed when parliament rose for the next election, but the cause was taken up again to the government by Aidy and other activists, and it passed the Transgender (Anti-Discrimination and Other Acts Amendment) Act of 1996 (NSW). This is the Act that made possible the later ruling in the High Court recognising non-binary sex (NSW Registrar of Births, Deaths and Marriages v Norrie [2014].

I first met Aidy at an early meeting of the Transgender Liberation Coalition (aka Transgender Lobby Coalition) in the early 1990s, when they gave me advice about finding a doctor who supported non-binary choices with regard to hormone therapy. Aidy was studying at UTS, which was hosting Queer Collaborations, so they invited me along to co-present some workshops on sex and gender. Aidy gave an academic dissection, and I did a little song and dance, show and tell. Everything I know about Foucault and post-modern deconstruction I learned second hand from Aidy.Aidy was fiercely intelligent, and spoke in a very quiet Irish voice. They were very street smart and politically savvy, and taught me a lot.

At Aidy’s instigation, the two of us took a proposal to the Sydney Star Observer for a regular column on gender and transgender issues, and this became Gender Agenda. We were hosted by Philip Adams on the panel of his ABC Radio National Late Show Live, along with avant-garde drag artiste Cindy Pastel and American feminist academic Jane Gallop. When Philip asked about their gender journey, Aidy replied,“ I took a taxi here”.

We took every opportunity to get in front of cameras and microphones to challenge gender norms and inspire social inclusion, and you can see and hear Aidy starring in the docudrama Sexing the Label, sitting on Gilligan's Island (corner Oxford and Flinders Street) as the 1996 Mardi Gras parade speeds by in fast motion.A nightclub in Kings Cross that was part of Abe Saffron’s network was accused of discriminating against a transgender woman. In response, Aidy negotiated with the nightclub network for a free venue to use for a fundraiser to benefit the trans community. This led to the 'Trany Pride' Ball at the old Les Girls nightclub, which raised money for the first 'Trany Pride' float in the Mardi Gras Parade. This helped build enough community support for the successful law reform achieved in 1996.

There aren’t many people as caring and intelligent as Aidy, and their passing is a devastating loss. But too, Aidy was part of many invigorating heady and sometimes terrifying adventures, memories to cherish, or to just wonder at how we survived them.

When the cameras started rolling on Phyllis Papps and Francesca Curtis in October 1970, both their lives and Australia would never be the same.

Fifty-one years ago, the pair made history by being the first lesbian couple to come out on national television, in an interview with the ABC's This Day Tonight.

"The early 1970s were very, very conservative ... Gay women were invisible, because people didn't think lesbians existed," Ms Papps says.

Ms Papps and Ms Curtis, who are still together and live on Victoria's Phillip Island, have once again shared their story.

p>In the documentary, Why Did She Have To Tell The World?, which premiered on Compass on Sunday, the pioneering women look back at their journey.'Nobody talked about it'

When Ms Papps and Ms Curtis were growing up, male homosexuality was illegal across Australia.

Legislation did not include lesbians, because, as Ms Papps reiterates, "they were invisible".

In this environment, both Ms Papps and Ms Curtis struggled immensely with their sexuality.

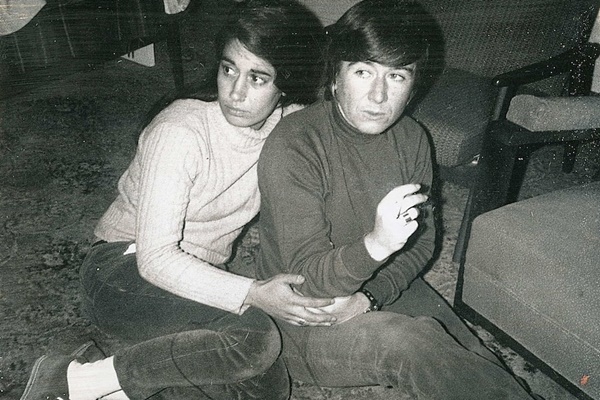

A black and white photo of Phyllis Papps and Francesca Curtis from the early 1970s.

Phyllis Papps and Francesca Curtis embrace in the early 1970s.(Supplied: The Australian Queer Archives)

"I didn't know anything about homosexuality or lesbianism. Nobody talked about it in those days," Ms Curtis tells the documentary. Ms Papps came from a very traditional Greek family and was briefly engaged to a man.

"I knew I was different, but I was forced to live a heterosexual life because my mother expected it of me and society did," she says.

A montage of images of the two lesbians who came out on national TV in 1970.

When Ms Papps confided to a colleague at work about her sexuality, the result did far more harm than good.

"[The colleague] gave me the names of three psychiatrists, and I went to one of them," she says.

"[I was given the drug] sodium pentothal, injected with it, and then had to talk."

Ms Papps and Ms Curtis met through activist circles and became prominent members of Australia's first homosexual political rights group, the Daughters of Bilitis, which later renamed itself the Australasian Lesbian Movement.

The pair exchanged wedding rings in July 1970 and in a matter of months, were known around the country.

Ms Papps and Ms Curtis agreed to take part in a story about lesbianism with the ABC's This Day Tonight to push for wider acceptance and visibility of the LGBTQIA+ community.

"No-one wanted to go on [the show], they were all in the closet, so Phyllis and I volunteered," Ms Curtis says.

Stand-in host Peter Couchman introduced the pair by saying, "most people find it hard to understand the kind of love that Phyllis and Francesca feel for each other".

"The law condones it, but many other women are revolted by the very thought of it and a lot of the churches regard it as perverted and unnatural," he told viewers.

Mr Couchman went on to ask Ms Curtis if she ever felt guilty about her sexuality.

She responded: "I think I had three months approximately of guilt. And then it went to a stage where I wanted to get up and I wanted to tell the world and I wanted the world to accept it."

Phyllis Papps and Francesca Curtis in a black and white photo taken during This Day Tonight in October 1970. The couple say the interview was a turning point — but came with a high personal cost.(ABC)

The impact of the national spotlight on Ms Papps and Ms Curtis was immediate.

"My mother took legal action against Francesca and myself to prevent us from making a claim on her inheritance," Ms Papps recalls.

"And my mother said, 'I'm happy to see you again, but I won't see both of you together' ... In our personal and professional lives, [This Day Tonight] was quite devastating."

But their TV appearance was heralded as ground-breaking and a key moment in Australia's long and unfinished road towards LGBTQIA+ equality.

"I believe This Day Tonight was absolutely major in creating a force," Ms Papps says.

Broader LGBTQIA+ progress happened slowly in the years following the interview.

South Australia became the first state to decriminalise male acts of homosexuality in 1975, but it was not until 1997 that Tasmania became the final Australian jurisdiction to do so.

And marriage equality would not pass federal parliament until 2017.

"It has been a life of struggle ... Not because we couldn't cope with being ourselves, [but because] we couldn't get people to accept us," Ms Papps says.

But throughout the difficulties, Ms Papps and Ms Curtis always had each other.

"You do have some highs and you do have some lows, and you stay together because you love each other, you care for each other ... you're great friends," Ms Papps says.

A changing AustraliaThe documentary's writer and director Abbie Pobjoy says they set out to "hold up a mirror to Phyllis and Francesca's national coming out 50 years ago".

"[I wanted] to showcase their hardships, triumphs and activism," they say.

"Now in the completion of the project, I realised that this story has also held up a mirror to myself, my fellow storytellers and the next generation of LGBTQIA+ young people and where we have to go next to secure our acceptance and livelihoods."

curtis4In recognition of their advocacy work, Ms Papps and Ms Curtis received a lifetime achievement award at the 2019 Australian LGBTI Awards, where they urged young people to continue the fight.

A group photo of the winners at the 2019 Australian LGBTI Awards, including Phyllis Papps and Francesca Curtis.

Phyllis and Francesca want the next generation to continue to build on their activism.(Supplied: Australian LGBTI Awards)

Looking back, Ms Papps says she has seen many examples of changing attitudes towards the LGBTQIA+ community, but one stands out.

It was during the marriage equality postal survey of 2017, when Australians were asked if they supported legalising same-sex marriage.

"My mum was in the nursing home, aged 98," she recalls.

In a very gentle way I said, 'Mum, how did you vote?' And proudly she said, 'I voted yes' ... They were almost her last words.

"It took a whole lifetime to get to that."

Tutu’s passing is a reminder of the ANC’s unfinished business

Tutu’s reconciliation efforts were supposed to be followed by justice for apartheid victims. That is yet to happen.

Sisonke Msimang Sisonke Msimang is a South African writer and political commentator who focuses on race, gender and democracy. Published On 27 Dec 2021

South African Archbishop Emeritus Desmond Tutu passed away at the age of 90 on December 26 [File: John Stillwell, Pool Photo via AP]M/p>

Archbishop Desmond Tutu, who passed away on December 26, was a tireless campaigner for justice. Though he officially retired in the mid-1990s, he never stopped haranguing those in power and expecting them to do better. As he famously said, “I wish I could shut up, but I can’t, and I won’t.” Over the course of his life, many of his opponents wished the same. Thankfully for South Africans of all ages, the Arch, as he was affectionately known, never learned to keep quiet.

There was no voice quite like his, and his passing is a reminder that the task of bringing justice to the racially traumatised nation he tried to help heal remains unfinished business. Tutu dedicated his life to non-racialism – a peculiarly South African phrase describing a utopian vision that went beyond equality and spoke to a deeper desire to connect with authenticity across racial, ethnic, class and gender divides.

Today nonracialism has fallen out of favour in the country. The kind of hope Tutu espoused is in short supply at the moment. In the last decade or so South Africans have lost their innocence and even the most ardent champions of racial and economic justice find it hard to call for much more than tolerance. For Tutu, of course, there was no room for such an anaemic response to social justice. His enthusiasm for ending oppression seeped out of him in tears and giggles and whoops; his love for people – “abantu” – was infectious.

Many people divide Tutu’s activism into two parts: his efforts to end apartheid (for which he won a Nobel Peace Prize in 1984 before the award lost some of its moral sheen); and his efforts to build a nation in which South Africans could embody the ideals of the Rainbow Nation he and his friend and comrade Nelson Mandela spoke of with such eloquence. He was widely admired for the former and was more controversial in respect of the latter although, of course, there was little difference between Tutu before and after South Africa’s freedom.

In the 1970s and 1980s, Tutu served as general secretary of the South African Council of Churches and thus occupied a crucial – and perhaps singular – space in the South African liberation movement. He was at the forefront of an era of marches and boycotts, but he was also called upon to minister to the grieving at scores of funerals in the bloodiest period of the South African conflict.

Those were grim times and Tutu was often at the centre of the fray. It was during this period that the now iconic image of Tutu emerged. He was often “a solitary figure in his purple cassock”, negotiating with police to let mourners express their pain.

It came as no surprise that Tutu was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize. In his acceptance speech he wondered if, “oppression dehumanises the oppressor as much as, if not more than, the oppressed”. He suggested that the oppressed and the oppressor “need each other to become truly free, to become human. We can be human only in fellowship, in community, in koinonia, in peace.”

A decade later his country was free, and Tutu was able to test his theory. In 1995, a year after the historic elections that ushered in the African National Congress (ANC) and put Mandela into the role of president, he was appointed as the chair of the country’s new Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC), a new entity designed as an experiment in collective healing.

Internationally, the TRC was widely acclaimed for prioritising reconciliation over revenge. At home, there were mixed feelings. On the one hand, the public hearings held by the commission modelled the kind of transparency that had never been seen before – apartheid thrived in the dark of course. On the other hand, Tutu’s insistence on forgiveness sometimes manifested as an institutional reluctance to pursue tougher forms of accountability than forgiveness.

As the TRC collected evidence of wrongdoings perpetrated under apartheid, Tutu wept and harangued and pleaded with witnesses, trying desperately to cajole them into admitting wrongdoing and asking for forgiveness. This was often charming and sometimes confounding.

In a now infamous series of exchanges, Tutu begged Winnie Madikizela-Mandela to apologise to Joyce Seipei, the mother of Stompie, a child she was alleged to have played a role in the killing of in the late 1980s. She apologised, though she was bitter about the exchange for years afterwards.

Today a generation of activists who know little else of Tutu and who hold up Madikizela-Mandela as their hero see Tutu as having been too hard on her. They are not wrong, of course. Still, Tutu was also scathing when it came to addressing former apartheid leaders, like FW De Klerk, who lied and withheld crucial information during their testimonies.

Tutu was neither made nor broken by the difficult exchanges that took place in the context of the TRC. He was a man with nothing to prove and he ran the commission with a deep sense of love and a commitment to truth-telling and forgiveness. This instinct sometimes overshadowed his country’s need for tangible justice, for perpetrators to serve time behind bars and for victims to be provided the details of where their loved ones had been killed.

In the end, however, the most important critiques of the TRC have little to do with Tutu. By focusing on the stories of the most obviously wounded – the relatives of the tortured and murdered – the commission missed an important opportunity to address the structural and systemic impact of apartheid. In other words, in spite of its harrowing stories and its scenes of spectacular grief, the TRC was never given a full mandate to address the group effects of apartheid – the loss of opportunity wrought on generations of Black people by naked racism.

To be sure it is almost impossible to tally such a loss. How do you add up the harms done and would an exact figure lessen the pain? The burden of answering this question falls on the new generation.

The TRC handed a list of apartheid operatives who were thought to have been involved in killing anti-apartheid activists to the National Prosecuting Authority. In the two decades since then, successive ANC governments have done nothing to bring those people to justice, nor have they ever agreed to address the question of redress and compensation for all the victims of apartheid.

The fault for this does not lie with Desmond Tutu. To the contrary, his death reminds us of the unfinished business of the transition from apartheid to democracy. This was not his business – it is ours.

The jaded among us would do well to heed the great man’s words. With his trademark bluntness, Tutu said, “If you want peace, you don’t talk to your friends. You talk to your enemies.” This insistence on reaching out and across all sorts of divides was the key to his effectiveness.

I am not sure I would be free to be me today had he not put on that purple robe day after day trying to make peace where only moments before there had been strife. For this I – and many South Africans, Black and white – owe him everything.

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Al Jazeera’s editorial stance.

Sisonke Msimang is a South African writer and political commentator who focuses on race, gender and democracy. Sisonke Msimang writes about South Africa, race, gender and democracy. She is the author of two books: Always Another Country: a memoir of exile and home, and The Resurrection of Winnie Mandela.

SPAIDS PART 1 - SYDNEY PARK AIDS MEMORIAL GROVES HOME PAGE